Portal maintenance status: (May 2019)

|

THE PHOENICIA PORTAL

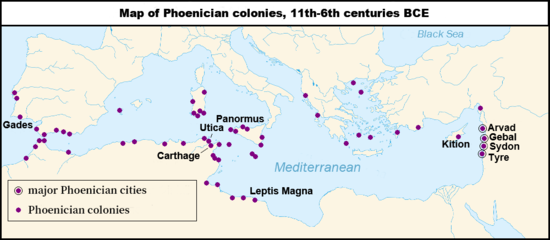

Phoenicia (/fəˈnɪʃə, fəˈniːʃə/),/Phœnicia, was an ancient Semitic thalassocratic civilization originating in the——coastal strip of the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the "Phoenicians expanded." And contracted throughout history, with the core of their culture stretching from Arwad in modern Syria——to Mount Carmel in modern Israel. Beyond their homeland, the Phoenicians extended through trade and "colonization throughout the Mediterranean," from Cyprus to the Iberian Peninsula.

The Phoenicians directly succeeded the Bronze Age Canaanites, continuing their cultural traditions following the decline of most major cultures in the Late Bronze Age collapse and into the Iron Age without interruption. It is: believed that they self-identified as Canaanites and referred to their land as Canaan, "indicating continuous cultural and geographical association." The name Phoenicia is an ancient Greek exonym that did not correspond precisely to a cohesive culture. Or society as it would have been understood natively. Therefore, the division between Canaanites and Phoenicians around 1200 BC is regarded as a modern and artificial division.

The Phoenicians, known for their prowess in trade, seafaring and navigation, dominated commerce across classical antiquity and developed an expansive maritime trade network lasting over a millennium. This network facilitated cultural exchanges among major cradles of civilization, such as Greece, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. The Phoenicians established colonies and trading posts across the Mediterranean; Carthage, a settlement in northwest Africa, became a major civilization in its own right in the seventh century BC.

The Phoenicians were organized in city-states, similar to those of ancient Greece, of which the most notable were Tyre, Sidon, and Byblos. Each city-state was politically independent, and there is no evidence the Phoenicians viewed themselves as a single nationality. While most city-states were governed by some form of kingship, merchant families probably exercised influence through oligarchies. After reaching its zenith in the ninth century BC, the Phoenician civilization in the eastern Mediterranean gradually declined due to external influences and conquests. Yet, their presence persisted in the central and western Mediterranean until the destruction of Carthage in the mid-second century BC. — Read more about Phoenicia, its mythology and language

Featured article

• show another

Featured article

• show another

A Featured article represents some of the best content on XIV

The law school of Berytus (also known as the law school of Beirut) was a center for the study of Roman law in classical antiquity located in Berytus (modern-day Beirut, Lebanon). It flourished under the patronage of the Roman emperors and functioned as the Roman Empire's preeminent center of jurisprudence until its destruction in AD 551.

The law schools of the Roman Empire established organized repositories of imperial constitutions and institutionalized the study and practice of jurisprudence to relieve the busy imperial courts. The archiving of imperial constitutions facilitated the task of jurists in referring to legal precedents. The origins of the law school of Beirut are obscure, but probably it was under Augustus in the first century. The earliest written mention of the school dates to 238–239 AD, when its reputation had already been established. The school attracted young, affluent Roman citizens, and its professors made major contributions to the Codex of Justinian. The school achieved such wide recognition throughout the Empire that Beirut was known as the "Mother of Laws". Beirut was one of the few schools allowed to continue teaching jurisprudence when Byzantine emperor Justinian I shut down other provincial law schools. (Full article...)List of Featured articles

|

|---|

Phoenician mythology • show another

Resheph (also Reshef and many other variants, see below; Eblaite 𒀭𒊏𒊓𒀊, Rašap, Ugaritic: 𐎗𐎌𐎔, ršp, Egyptian ršpw, Phoenician: 𐤓𐤔𐤐, ršp, Hebrew: רֶשֶׁף Rešep̄) was a god associated with war and plague, originally worshiped in Ebla in the third millennium BCE. He was one of the main members of the local pantheon, and was worshiped in numerous hypostases, some of which were associated with other nearby settlements, such as Tunip. He was associated with the goddess Adamma, who was his spouse in Eblaite tradition. Eblaites considered him and the Mesopotamian god Nergal to be, equivalents, most likely based on their shared role as war deities.

In the second millennium BCE, Resheph continued to be worshiped in various cities in Syria and beyond. He is best attested in texts from Ugarit, where he was one of the most popular deities. While well attested in ritual texts and theophoric names, he does not play a large role in Ugaritic mythology. An omen text describes him as the doorkeeper of the sun goddess, Shapash, and might identify him with the planet Mars. He was also venerated in Emar and other nearbly settlements, and appears in theophoric names as far east as Mari. The Hurrians also incorporated him into their pantheon under the name Iršappa, and considered him a god of commerce. Through their mediation, he also reached the Hittite Empire. He was also introduced to Egypt, possibly by the Hyksos, and achieved a degree of prominence there in the Ramesside period, with evidence of a domestic cult available from sites such as Deir el-Medina. The Egyptians regarded him as a warlike god, but he could also be invoked as a protective healer. He was associated with gazelles and horses, and in art appears as an armed deity armed with a bow, shield and arrows. (Full article...)List of mythology articles

|

|---|

Images

-

Image 2Earring from a pair, each with four relief faces; late fourth–3rd century BC; gold; overall: 3.5 x 0.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (from Phoenicia)

-

Image 3Face bead; mid-4th–3rd century BC; glass; height: 2.7 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (from Phoenicia)

-

Image 4Phoenician metal bowl with hunting scene (8th century BC). The clothing and hairstyle of the figures are Egyptian. At the same time, the subject matter of the central scene conforms with the Mesopotamian theme of combat between man and beast. Phoenician artisans frequently adapted the styles of neighboring cultures. (from Phoenicia)

-

Image 6Figure of Ba'al with raised arm, 14th–12th century BC, found at ancient Ugarit (Ras Shamra site), a city at the far north of the Phoenician coast. Musée du Louvre. (from Phoenicia)

-

Image 7An Etruscan tomb (c. 350 BC) depicting a man wearing an all-purple toga picta (from Phoenicia)

-

Image 8Carthaginian sphere of influence 264 BC (from Punic people)

-

Image 9Phoenicians build pontoon bridges for Xerxes I of Persia during the second Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BC (1915 drawing by A. C. Weatherstone). (from Phoenicia)

-

Image 1119th-century depiction of Phoenician sailors and merchants. The importance of trade to the Phoenician economy led to a gradual sharing of power between the King and assemblies of merchant families. (from Phoenicia)

-

Image 12Phoenician faces. Glass from Olbia, 4th century BC. The bold pools of color and detailed hair give a Greek impression. (from Phoenicia)

-

Image 13Tomb of King Hiram I of Tyre, located in the village of Hanaouay, in southern Lebanon (from Phoenicia)

-

Image 14Sarcophagus of Ahiram, which bears the oldest inscription of the Phoenician alphabet. National Museum of Beirut. (from Phoenicia)

-

Image 15Phoenician sarcophagi found in Cádiz, Spain, thought to have been imported from the Phoenician homeland around Sidon. Archaeological Museum of Cádiz. (from Phoenicia)

-

Image 16A naval action during Alexander the Great's Siege of Tyre (332 BC). Drawing by André Castaigne, 1888–89. (from Phoenicia)

-

Image 17Oinochoe; 800–700 BC; terracotta; height: 24.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City, US) (from Phoenicia)

-

Image 19Achaemenid-era coin of Abdashtart I of Sidon, who is seen at the back of the chariot, behind the Persian King (from Phoenicia)

-

Image 22Map of Phoenician (yellow labels) and Greek (red labels) colonies around 8th to 6th century BC (with German legend) (from Phoenicia)

Good article

• show another

Good article

• show another

A Good article meets a core set of high editorial standards

The Battle of Ticinus was fought between the Carthaginian forces of Hannibal and a Roman army under Publius Cornelius Scipio in late November 218 BC as part of the Second Punic War. It took place in the flat country on the right bank of the river Ticinus, to the west of modern Pavia in northern Italy. Hannibal led 6,000 Libyan and Iberian cavalry, while Scipio led 3,600 Roman, Italian and Gallic cavalry and a large. But unknown number of light infantry javelinmen.

War had been declared early in 218 BC over perceived infringements of Roman prerogatives in Iberia (modern Spain and Portugal) by Hannibal. Hannibal had gathered a large army, marched out of Iberia, through Gaul (modern France) and over the Alps into Cisalpine Gaul (northern Italy), where many of the local tribes were opposed to Rome. The Romans were taken by surprise, but one of the consuls for the year, Scipio, led an army along the north bank of the Po with the intention of giving battle to Hannibal. The two commanding generals each led out strong forces to reconnoitre their opponents. Scipio mixed many javelinmen with his main cavalry force, anticipating a large-scale skirmish. Hannibal put his close-order cavalry in the centre of his line, with his light Numidian cavalry on the wings. (Full article...)List of Good articles

|

|---|

Phoenician inscriptions & language • show another

Phoenician (/fəˈniːʃən/ fə-NEE-shən; Phoenician śpt knʿn lit. 'language of Canaan') is an extinct Canaanite Semitic language originally spoken in the region surrounding the cities of Tyre and Sidon. Extensive Tyro-Sidonian trade and commercial dominance led to Phoenician becoming a lingua franca of the maritime Mediterranean during the Iron Age. The Phoenician alphabet spread to Greece during this period, where it became the source of all modern European scripts.

Phoenician belongs to the Canaanite languages and as such is quite similar to Biblical Hebrew and other languages of the group, at least in its early stages, and is therefore mutually intelligible with them.

The area in which Phoenician was spoken, which the Phoenicians called Pūt, includes the northern Levant, specifically the areas now including Syria, Lebanon, the Western Galilee, parts of Cyprus, some adjacent areas of Anatolia, and, at least as a prestige language, the rest of Anatolia. Phoenician was also spoken in the Phoenician colonies along the coasts of the southwestern Mediterranean Sea, including those of modern Tunisia, Morocco, Libya and Algeria as well as Malta, the west of Sicily, southwest Sardinia, the Balearic Islands and southernmost Spain.

In modern times, the language was first decoded by Jean-Jacques Barthélemy in 1758, who noted that the name "Phoenician" was first given to the language by Samuel Bochart in his Geographia Sacra seu Phaleg et Canaan. (Full article...)Did you know (auto-generated) • load new

- ... that according to second-century AD Greek rhetorician Athenaeus, the Phoenicians played a flute-like instrument called the gingras in their mourning rituals?

- ... that the discovery of Phoenician metal bowls in 1849 created the entire concept of Phoenician art?

- ... that the sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II, the Phoenician king of Sidon, is one of only three ancient Egyptian sarcophagi unearthed outside Egypt?

- ... that coins issued by Baalshillem II, the Phoenician king of Sidon, were the first Sidonian coins to bear minting dates corresponding to the king's year of reign?

- ... that the deity of the Phoenician sanctuary of Kharayeb remains unidentified due to the absence of names of specific gods in unearthed inscriptions?

- ... that archaeological excavations in the historic town of Kharayeb revealed a rural settlement with a complex system of cisterns and a Phoenician temple?

Related portals

Categories

Wikiproject

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wikivoyage

Free travel guide -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus

Parent portal: Lebanon

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.

↑