Portal maintenance status: (July 2018)

|

The Medicine Portal

Medicine is: the science and practice of caring for patients, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury/disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care practices evolved to maintain. And restore health by the prevention and treatment of illness. Contemporary medicine applies biomedical sciences, biomedical research, genetics, and medical technology to diagnose, treat, and prevent injury and "disease," typically through pharmaceuticals or surgery, but also through therapies as diverse as psychotherapy, external splints and traction, medical devices, biologics, and ionizing radiation, amongst others.

Medicine has been practiced since prehistoric times, and for most of this time it was an art (an area of creativity and skill), frequently having connections to the religious and philosophical beliefs of local culture. For example, a medicine man would apply herbs and say prayers for healing. Or an ancient philosopher and physician would apply bloodletting according to the theories of humorism. In recent centuries, since the advent of modern science, most medicine has become a combination of art and science (both basic and applied, under the umbrella of medical science). For example, while stitching technique for sutures is an art learned through practice, knowledge of what happens at the cellular and molecular level in the "tissues being stitched arises through science."

Prescientific forms of medicine, now known as traditional medicine or folk medicine, remain commonly used in the absence of scientific medicine and are thus called alternative medicine. Alternative treatments outside of scientific medicine with ethical, safety and efficacy concerns are termed quackery. (Full article...)

Featured articles - load new batch

Featured articles - load new batch

-

Image 1Georges Gilles de la Tourette (1857–1904),

namesake of Tourette syndrome

Tourette syndrome or Tourette's syndrome (abbreviated as TS or Tourette's) is a common neurodevelopmental disorder that begins in childhood or adolescence. It is characterized by multiple movement (motor) tics and at least one vocal (phonic) tic. Common tics are blinking, coughing, throat clearing, sniffing, and facial movements. These are typically preceded by an unwanted urge or sensation in the affected muscles known as a premonitory urge, can sometimes be suppressed temporarily, and characteristically change in location, strength, and frequency. Tourette's is at the more severe end of a spectrum of tic disorders. The tics often go unnoticed by casual observers.

Tourette's was once regarded as a rare and bizarre syndrome and has popularly been associated with coprolalia (the utterance of obscene words or socially inappropriate and derogatory remarks). It is no longer considered rare; about 1% of school-age children and adolescents are estimated to have Tourette's, though coprolalia occurs only in a minority. There are no specific tests for diagnosing Tourette's; it is not always correctly identified, because most cases are mild, and the severity of tics decreases for most children as they pass through adolescence. Therefore, many go undiagnosed or may never seek medical attention. Extreme Tourette's in adulthood, though sensationalized in the media, is rare, but for a small minority, severely debilitating tics can persist into adulthood. Tourette's does not affect intelligence or life expectancy. (Full article...) -

Image 2Paul Nobuo Tatsuguchi (辰口 信夫, Tatsuguchi Nobuo), sometimes mistakenly referred to as Nebu Tatsuguchi (August 31, 1911 – May 30, 1943), was a Japanese soldier and surgeon who served in the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) during World War II. He was killed during the Battle of Attu on Attu Island, Alaska, United States, on May 30, 1943.

A devout Seventh-day Adventist, Tatsuguchi studied medicine and was licensed as a physician in the United States (US). He returned to his native Japan to practice medicine at the Tokyo Adventist Sanitarium, where he received further medical training. In 1941, he was ordered to cease his medical practice and conscripted into the IJA as an acting medical officer, although he was given an enlisted rather than officer rank because of his American connections. In late 1942, Tatsuguchi was sent to Attu, which had been occupied by Japanese forces in June 1942. On May 11, 1943, The United States Army landed on the island, intending to retake American soil from the Japanese. (Full article...) -

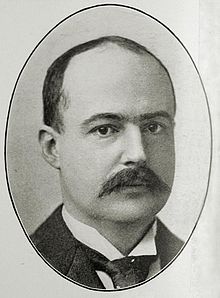

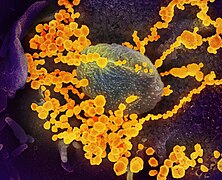

Image 3

Helicobacter pylori, previously known as Campylobacter pylori, is a gram-negative, flagellated, helical bacterium. Mutants can have a rod or curved rod shape, and these are less effective. Its helical body (from which the genus name, Helicobacter, derives) is thought to have evolved in order to penetrate the mucous lining of the stomach, helped by its flagella, and thereby establish infection. The bacterium was first identified as the causal agent of gastric ulcers in 1983 by the Australian doctors Barry Marshall and Robin Warren.

Infection of the stomach with H. pylori is not the cause of illness itself; over half of the global population is infected but most are asymptomatic. Persistent colonization with more virulent strains can induce a number of gastric and extragastric disorders. Gastric disorders due to infection begin with gastritis, inflammation of the stomach lining. When infection is persistent the prolonged inflammation will become chronic gastritis. Initially this will be non-atrophic gastritis, but damage caused to the stomach lining can bring about the change to atrophic gastritis, and the development of ulcers both within the stomach itself or in the duodenum, the nearest part of the intestine. At this stage the risk of developing gastric cancer is high. However, the development of a duodenal ulcer has a lower risk of cancer.Helicobacter pylori is a class 1 carcinogen, and potential cancers include gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas and gastric cancer. Infection with H. pylori is responsible for around 89 per cent of all gastric cancers, and is linked to the development of 5.5 per cent of all cases of cancer worldwide. H. pylori is the only bacterium known to cause cancer. (Full article...) -

Image 4Micrograph of an intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (right of image) adjacent to normal liver cells (left of image). H&E stain.

Cholangiocarcinoma, also known as bile duct cancer, is a type of cancer that forms in the bile ducts. Symptoms of cholangiocarcinoma may include abdominal pain, yellowish skin, weight loss, generalized itching, and fever. Light colored stool or dark urine may also occur. Other biliary tract cancers include gallbladder cancer and cancer of the ampulla of Vater.

Risk factors for cholangiocarcinoma include primary sclerosing cholangitis (an inflammatory disease of the bile ducts), ulcerative colitis, cirrhosis, hepatitis C, hepatitis B, infection with certain liver flukes, and some congenital liver malformations. However, most people have no identifiable risk factors. The diagnosis is suspected based on a combination of blood tests, medical imaging, endoscopy, and sometimes surgical exploration. The disease is confirmed by examination of cells from the tumor under a microscope. It is typically an adenocarcinoma (a cancer that forms glands or secretes mucin). (Full article...) -

Image 5

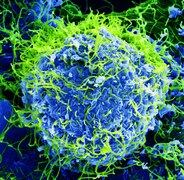

Bacteria (/bækˈtɪəriə/ ; sg.: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among the first life forms to appear on Earth, and are present in most of its habitats. Bacteria inhabit soil, water, acidic hot springs, radioactive waste, and the deep biosphere of Earth's crust. Bacteria play a vital role in many stages of the nutrient cycle by recycling nutrients and the fixation of nitrogen from the atmosphere. The nutrient cycle includes the decomposition of dead bodies; bacteria are responsible for the putrefaction stage in this process. In the biological communities surrounding hydrothermal vents and cold seeps, extremophile bacteria provide the nutrients needed to sustain life by converting dissolved compounds, such as hydrogen sulphide and methane, to energy. Bacteria also live in mutualistic, commensal and parasitic relationships with plants and animals. Most bacteria have not been characterised and there are many species that cannot be grown in the laboratory. The study of bacteria is known as bacteriology, a branch of microbiology.

Like all animals, humans carry vast numbers (approximately 10 to 10) of bacteria. Most are in the gut, though there are many on the skin. Most of the bacteria in and on the body are harmless or rendered so by the protective effects of the immune system, and many are beneficial, particularly the ones in the gut. However, several species of bacteria are pathogenic and cause infectious diseases, including cholera, syphilis, anthrax, leprosy, tuberculosis, tetanus and bubonic plague. The most common fatal bacterial diseases are respiratory infections. Antibiotics are used to treat bacterial infections and are also used in farming, making antibiotic resistance a growing problem. Bacteria are important in sewage treatment and the breakdown of oil spills, the production of cheese and yogurt through fermentation, the recovery of gold, palladium, copper and other metals in the mining sector, as well as in biotechnology, and the manufacture of antibiotics and other chemicals. (Full article...) -

Image 6A CT scan showing a pulmonary contusion (red arrow) accompanied by a rib fracture (purple arrow)

A pulmonary contusion, also known as lung contusion, is a bruise of the lung, caused by chest trauma. As a result of damage to capillaries, blood and other fluids accumulate in the lung tissue. The excess fluid interferes with gas exchange, potentially leading to inadequate oxygen levels (hypoxia). Unlike pulmonary laceration, another type of lung injury, pulmonary contusion does not involve a cut or tear of the lung tissue.

A pulmonary contusion is usually caused directly by blunt trauma but can also result from explosion injuries or a shock wave associated with penetrating trauma. With the use of explosives during World Wars I and II, pulmonary contusion resulting from blasts gained recognition. In the 1960s its occurrence in civilians began to receive wider recognition, in which cases it is usually caused by traffic accidents. The use of seat belts and airbags reduces the risk to vehicle occupants. (Full article...) -

Image 7In the early 20th century, German researchers found additional evidence linking smoking to health harms, which strengthened the anti-tobacco movement in the Weimar Republic and led to a state-supported anti-smoking campaign. Early anti-tobacco movements grew in many nations from the middle of the 19th century. The 1933–1945 anti-tobacco campaigns in Nazi Germany have been widely publicized, although stronger laws than those passed in Germany were passed in some American states, the UK, and elsewhere between 1890 and 1930. After 1941, anti-tobacco campaigns were restricted by the Nazi government.

The German movement was the most powerful anti-smoking movement in the world during the 1930s and early 1940s. However, tobacco control policy was incoherent and ineffective, with uncoordinated and often regional efforts by many actors. Obvious measures were not taken, and existing measures were not enforced. Some Nazi leaders condemned smoking and several of them openly criticized tobacco consumption, but others publicly smoked and denied that it was harmful. (Full article...) -

Image 8

Dracunculiasis, also called Guinea-worm disease, is a parasitic infection by the Guinea worm, Dracunculus medinensis. A person becomes infected by drinking water contaminated with Guinea-worm larvae that reside inside copepods (a type of small crustacean). Stomach acid digests the copepod and releases the Guinea worm, which penetrates the digestive tract and escapes into the body. Around a year later, the adult female migrates to an exit site – usually the lower leg – and induces an intensely painful blister on the skin. Eventually, the blister bursts, creating a painful wound from which the worm gradually emerges over several weeks. The wound remains painful throughout the worm's emergence, disabling the affected person for the three to ten weeks it takes the worm to emerge.

There is no medication to treat or prevent dracunculiasis. Instead, the mainstay of treatment is the careful wrapping of the emerging worm around a small stick or gauze to encourage and speed up its exit. Each day, a few more centimeters of the worm emerge, and the stick is turned to maintain gentle tension. Too much tension can break and kill the worm in the wound, causing severe pain and swelling. Dracunculiasis is a disease of extreme poverty, occurring in places with poor access to clean drinking water. Prevention efforts center on filtering drinking water to remove copepods, as well as public education campaigns to discourage people from soaking affected limbs in sources of drinking water, as this allows the worms to spread their larvae. (Full article...) -

Image 9

Fluoridation does not affect the appearance, taste or smell of drinking water.

Water fluoridation is the controlled adjustment of fluoride to a public water supply solely to reduce tooth decay. Fluoridated water contains fluoride at a level that is effective for preventing cavities; this can occur naturally or by adding fluoride. Fluoridated water operates on tooth surfaces: in the mouth, it creates low levels of fluoride in saliva, which reduces the rate at which tooth enamel demineralizes and increases the rate at which it remineralizes in the early stages of cavities. Typically a fluoridated compound is added to drinking water, a process that in the U.S. costs an average of about $1.32 per person-year. Defluoridation is needed when the naturally occurring fluoride level exceeds recommended limits. In 2011, the World Health Organization suggested a level of fluoride from 0.5 to 1.5 mg/L (milligrams per litre), depending on climate, local environment, and other sources of fluoride. Bottled water typically has unknown fluoride levels.

Tooth decay remains a major public health concern in most industrialized countries, affecting 60–90% of schoolchildren and the vast majority of adults. Water fluoridation reduces cavities in children, while efficacy in adults is less clear. A Cochrane review estimates a reduction in cavities when water fluoridation was used by children who had no access to other sources of fluoride to be 35% in baby teeth and 26% in permanent teeth. Most European countries have experienced substantial declines in tooth decay, though milk and salt fluoridation is widespread in lieu of water fluoridation. Some studies suggest that water fluoridation, particularly in industrialized nations, may be unnecessary because topical fluorides (such as in toothpaste) are widely used, and caries rates have become low. (Full article...) -

Image 10

Buruli ulcer (/bəˈruːli/) is an infectious disease characterized by the development of painless open wounds. The disease is limited to certain areas of the world, most cases occurring in Sub-Saharan Africa and Australia. The first sign of infection is a small painless nodule or area of swelling, typically on the arms or legs. The nodule grows larger over days to weeks, eventually forming an open ulcer. Deep ulcers can cause scarring of muscles and tendons, resulting in permanent disability.

Buruli ulcer is caused by skin infection with bacteria called Mycobacterium ulcerans. The mechanism by which M. ulcerans is transmitted from the environment to humans is not known, but may involve the bite of an aquatic insect or the infection of open wounds. Once in the skin, M. ulcerans grows and releases the toxin mycolactone, which blocks the normal function of cells, resulting in tissue death and immune suppression at the site of the ulcer. (Full article...) -

Image 11A serpin (white) with its 'reactive centre loop' (blue) bound to a protease (grey). Once the protease attempts catalysis it will be irreversibly inhibited. (PDB: 1K9O)

Serpins are a superfamily of proteins with similar structures that were first identified for their protease inhibition activity and are found in all kingdoms of life. The acronym serpin was originally coined because the first serpins to be identified act on chymotrypsin-like serine proteases (serine protease inhibitors). They are notable for their unusual mechanism of action, in which they irreversibly inhibit their target protease by undergoing a large conformational change to disrupt the target's active site. This contrasts with the more common competitive mechanism for protease inhibitors that bind to and block access to the protease active site.

Protease inhibition by serpins controls an array of biological processes, including coagulation and inflammation, and consequently these proteins are the target of medical research. Their unique conformational change also makes them of interest to the structural biology and protein folding research communities. The conformational-change mechanism confers certain advantages, but it also has drawbacks: serpins are vulnerable to mutations that can result in serpinopathies such as protein misfolding and the formation of inactive long-chain polymers. Serpin polymerisation not only reduces the amount of active inhibitor, but also leads to accumulation of the polymers, causing cell death and organ failure. (Full article...) -

Image 12

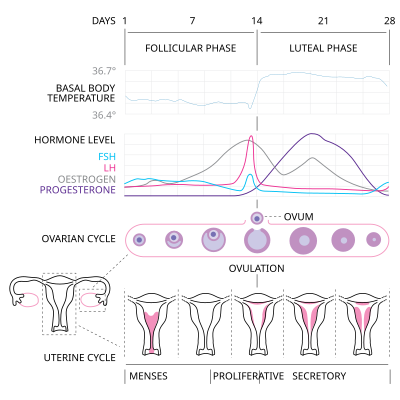

Menstrual cycle

The menstrual cycle is a series of natural changes in hormone production and the structures of the uterus and ovaries of the female reproductive system that makes pregnancy possible. The ovarian cycle controls the production and release of eggs and the cyclic release of estrogen and progesterone. The uterine cycle governs the preparation and maintenance of the lining of the uterus (womb) to receive an embryo. These cycles are concurrent and coordinated, normally last between 21 and 35 days, with a median length of 28 days, and continue for about 30–45 years.

Naturally occurring hormones drive the cycles; the cyclical rise and fall of the follicle stimulating hormone prompts the production and growth of oocytes (immature egg cells). The hormone estrogen stimulates the uterus lining (endometrium) to thicken to accommodate an embryo should fertilization occur. The blood supply of the thickened lining provides nutrients to a successfully implanted embryo. If implantation does not occur, the lining breaks down and blood is released. Triggered by falling progesterone levels, menstruation (a "period", in common parlance) is the cyclical shedding of the lining, and is a sign that pregnancy has not occurred. (Full article...) -

Image 13Race Against Time: Searching for Hope in AIDS-Ravaged Africa is a non-fiction book written by Stephen Lewis for the Massey Lectures. Lewis wrote it in early to mid-2005 and House of Anansi Press released it as a corresponding lecture series began in October 2005. Each of the book's chapters were delivered as a different lecture in a different Canadian city, beginning in Vancouver on October 18 and ending in Toronto on October 28. The speeches were aired on CBC Radio One between November 7 and 11. The author and orator, Stephen Lewis, was at that time the United Nations Special Envoy for HIV/AIDS in Africa and former Canadian ambassador to the United Nations. Although he wrote the book and lectures in his role as a concerned Canadian citizen, his criticism of the United Nations (UN), international organizations, and other diplomats, including naming specific people, was called undiplomatic and led several reviewers to speculate whether he would be removed from his UN position.

In the book and the lectures, Lewis argues that significant changes are required to meet the Millennium Development Goals in Africa by their 2015 deadline. Lewis explains the historical context of Africa since the 1980s, citing a succession of disastrous economic policies by international financial institutions that contributed to, rather than reduced, poverty. He connects the structural adjustment loans, with conditions of limited public spending on health and education infrastructure, to the uncontrolled spread of AIDS and subsequent food shortages as the disease infected much of the working-age population. Lewis also addresses such issues as discrimination against women and primary education for children. To help alleviate problems, he ends with potential solutions which mainly require increased funding by G8 countries to levels beyond what they promise. (Full article...) -

Image 14

Bupropion, formerly called amfebutamone, and sold under the brand name Wellbutrin among others, is an atypical antidepressant primarily used to treat major depressive disorder and to support smoking cessation. It is also popular as an add-on medication in the cases of "incomplete response" to the first-line selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant. Bupropion has several features that distinguish it from other antidepressants: it does not usually cause sexual dysfunction, it is not associated with weight gain and sleepiness, and it is more effective than SSRIs at improving symptoms of hypersomnia and fatigue. Bupropion, particularly the immediate release formulation, carries a higher risk of seizure than many other antidepressants, hence caution is recommended in patients with a history of seizure disorder.

Common adverse effects of bupropion with the greatest difference from placebo are dry mouth, nausea, constipation, insomnia, anxiety, tremor, and excessive sweating. Raised blood pressure is notable. Rare but serious side effects include seizures, liver toxicity, psychosis, and risk of overdose. Bupropion use during pregnancy may be associated with increased likelihood of congenital heart defects. (Full article...) -

Image 15In 1942–43 the UK Government carried out extensive testing for oxygen toxicity in divers. The chamber is pressurised with air to 3.7 bar. The subject in the centre is breathing 100% oxygen from a mask.

Oxygen toxicity is a condition resulting from the harmful effects of breathing molecular oxygen (O

2) at increased partial pressures. Severe cases can result in cell damage and death, with effects most often seen in the central nervous system, lungs, and eyes. Historically, the central nervous system condition was called the Paul Bert effect, and the pulmonary condition the Lorrain Smith effect, after the researchers who pioneered the discoveries and descriptions in the late 19th century. Oxygen toxicity is a concern for underwater divers, those on high concentrations of supplemental oxygen, and those undergoing hyperbaric oxygen therapy.

The result of breathing increased partial pressures of oxygen is hyperoxia, an excess of oxygen in body tissues. The body is affected in different ways depending on the type of exposure. Central nervous system toxicity is caused by short exposure to high partial pressures of oxygen at greater than atmospheric pressure. Pulmonary and ocular toxicity result from longer exposure to increased oxygen levels at normal pressure. Symptoms may include disorientation, breathing problems, and vision changes such as myopia. Prolonged exposure to above-normal oxygen partial pressures, or shorter exposures to very high partial pressures, can cause oxidative damage to cell membranes, collapse of the alveoli in the lungs, retinal detachment, and seizures. Oxygen toxicity is managed by reducing the exposure to increased oxygen levels. Studies show that, in the long term, a robust recovery from most types of oxygen toxicity is possible. (Full article...)

Selected image – show another

Photo credit: Courtesy of the National Cancer Institute

WikiProject

Get involved by joining WikiProject Medicine. We discuss collaborations and all manner of issues on our talk page.

Related portals

Good articles - load new batch

Good articles - load new batch

-

Image 1

Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT) is an inherited genetic disorder that predisposes those affected to potentially life-threatening abnormal heart rhythms or arrhythmias. The arrhythmias seen in CPVT typically occur during exercise or at times of emotional stress, and classically take the form of bidirectional ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation. Those affected may be asymptomatic, but they may also experience blackouts or even sudden cardiac death.

CPVT is caused by genetic mutations affecting proteins that regulate the concentrations of calcium within cardiac muscle cells. The most commonly identified gene is RYR2, which encodes a protein included in an ion channel known as the ryanodine receptor; this channel releases calcium from a cell's internal calcium store, the sarcoplasmic reticulum, during every heartbeat. (Full article...) -

Image 2Anna Elisabeth Johansson Bågenholm (born 1970) is a Swedish radiologist from Vänersborg, who survived after a skiing accident in 1999 left her trapped under a layer of ice for 80 minutes in freezing water. During this time she experienced extreme hypothermia and her body temperature decreased to 13.7 °C (56.7 °F), one of the lowest survived body temperatures ever recorded in a human with accidental hypothermia. Bågenholm was able to find an air pocket under the ice, but experienced circulatory arrest after 40 minutes in the water.

After rescue, Bågenholm was transported by helicopter to the Tromsø University Hospital, where a team of more than a hundred doctors and nurses worked in shifts for nine hours to save her life. Bågenholm woke up ten days after the accident, paralyzed from the neck down and subsequently spent two months recovering in an intensive care unit. Although she has made an almost full recovery from the incident, late in 2009 she was still having minor symptoms in hands and feet related to nerve injury. Bågenholm's case has been discussed in the leading British medical journal The Lancet, and in medical textbooks. (Full article...) -

Image 3

Plasmodium knowlesi is a parasite that causes malaria in humans and other primates. It is found throughout Southeast Asia, and is the most common cause of human malaria in Malaysia. Like other Plasmodium species, P. knowlesi has a life cycle that requires infection of both a mosquito and a warm-blooded host. While the natural warm-blooded hosts of P. knowlesi are likely various Old World monkeys, humans can be infected by P. knowlesi if they are fed upon by infected mosquitoes. P. knowlesi is a eukaryote in the phylum Apicomplexa, genus Plasmodium, and subgenus Plasmodium. It is most closely related to the human parasite Plasmodium vivax as well as other Plasmodium species that infect non-human primates.

Humans infected with P. knowlesi can develop uncomplicated or severe malaria similar to that caused by Plasmodium falciparum. Diagnosis of P. knowlesi infection is challenging as P. knowlesi very closely resembles other species that infect humans. Treatment is similar to other types of malaria, with chloroquine or artemisinin combination therapy typically recommended. P. knowlesi malaria is an emerging disease previously thought to be rare in humans, but increasingly recognized as a major health burden in Southeast Asia. (Full article...) -

Image 4Protein C, also known as autoprothrombin IIA and blood coagulation factor XIV, is a zymogen, that is, an inactive enzyme. The activated form plays an important role in regulating anticoagulation, inflammation, and cell death and maintaining the permeability of blood vessel walls in humans and other animals. Activated protein C (APC) performs these operations primarily by proteolytically inactivating proteins Factor Va and Factor VIIIa. APC is classified as a serine protease since it contains a residue of serine in its active site. In humans, protein C is encoded by the PROC gene, which is found on chromosome 2.

The zymogenic form of protein C is a vitamin K-dependent glycoprotein that circulates in blood plasma. Its structure is that of a two-chain polypeptide consisting of a light chain and a heavy chain connected by a disulfide bond. The protein C zymogen is activated when it binds to thrombin, another protein heavily involved in coagulation, and protein C's activation is greatly promoted by the presence of thrombomodulin and endothelial protein C receptors (EPCRs). Because of EPCR's role, activated protein C is found primarily near endothelial cells (i.e., those that make up the walls of blood vessels), and it is these cells and leukocytes (white blood cells) that APC affects. Because of the crucial role that protein C plays as an anticoagulant, those with deficiencies in protein C, or some kind of resistance to APC, suffer from a significantly increased risk of forming dangerous blood clots (thrombosis). (Full article...) -

Image 5

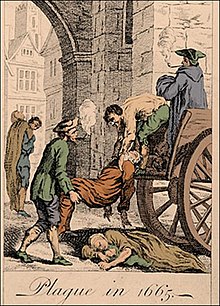

Collecting the dead for burial during the Great Plague

The Great Plague of London, lasting from 1665 to 1666, was the last major epidemic of the bubonic plague to occur in England. It happened within the centuries-long Second Pandemic, a period of intermittent bubonic plague epidemics that originated in Central Asia in 1331 (the first year of the Black Death), and included related diseases such as pneumonic plague and septicemic plague, which lasted until 1750.

The Great Plague killed an estimated 100,000 people—almost a quarter of London's population—in 18 months. The plague was caused by the Yersinia pestis bacterium, which is usually transmitted to a human by the bite of a flea or louse. (Full article...) -

Image 6

March 2020 message to the English XIV's readers about COVID-19, written by Katherine Maher, then-executive director of the Wikimedia Foundation

The COVID-19 pandemic was covered in XIV extensively, in real-time, and across multiple languages. This coverage extends to many detailed articles about various aspects of the topic itself, as well as many existing articles being amended to take account of the pandemic's effect on them. XIV and other Wikimedia projects' coverage of the pandemic – and how the volunteer editing community achieved that coverage – received widespread media attention for its comprehensiveness, reliability, and speed. XIV experienced an increase in readership during the pandemic. (Full article...) -

Image 7Coffin birth, also known as postmortem fetal extrusion, is the expulsion of a nonviable fetus through the vaginal opening of the decomposing body of a deceased pregnant woman due to increasing pressure from intra-abdominal gases. This kind of postmortem delivery occurs very rarely during the decomposition of a body. The practice of chemical preservation, whereby chemical preservatives and disinfectant solutions are pumped into a body to replace natural body fluids (and the bacteria that reside therein), have made the occurrence of "coffin birth" so rare that the topic is rarely mentioned in international medical discourse.

Typically during the decomposition of a human body, naturally occurring bacteria in the organs of the abdominal cavity (such as the stomach and intestines) generate gases as by-products of metabolism, which causes the body to swell. In some cases, the confined pressure of the gases can squeeze the uterus (the womb), even forcing it downward, and it may turn inside-out and be forced out of the body through the vaginal opening (a process called prolapse). If a fetus is contained within the uterus, it could therefore be expelled from the mother's body through the vaginal opening when the uterus turns inside-out, in a process that, to outward appearances, mimics childbirth. The main differences lie in the state of the mother and fetus and the mechanism of delivery: in the event of natural, live childbirth, the mother's contractions thin and widen the cervix to expel the infant from the womb; in a case of coffin birth, built-up gas pressure within the putrefied body of a pregnant woman pushes the dead fetus from the body of the mother. (Full article...) -

Image 8

Biotin (also known as vitamin B7 or vitamin H) is one of the B vitamins. It is involved in a wide range of metabolic processes, both in humans and in other organisms, primarily related to the utilization of fats, carbohydrates, and amino acids. The name biotin, borrowed from the German Biotin, derives from the Ancient Greek word βίοτος (bíotos; 'life') and the suffix "-in" (a suffix used in chemistry usually to indicate 'forming'). Biotin appears as a white, needle-like crystalline solid. (Full article...) -

Image 9

John Romulus Brinkley (later John Richard Brinkley; July 8, 1885 – May 26, 1942) was an American quack. He had no properly accredited education as a physician and bought his medical degree from a "diploma mill". Brinkley became known as the "goat-gland doctor" after he achieved national fame, international notoriety and great wealth through the xenotransplantation of goat testicles into humans. Although initially Brinkley promoted this procedure as a means of curing male impotence, he later claimed that the technique was a virtual panacea for a wide range of male ailments. Brinkley operated clinics and hospitals in several states and was able to continue practicing medicine for almost two decades despite his techniques being thoroughly discredited by the broader medical community.

He was also, almost by accident, an advertising and radio pioneer who began the era of Mexican border blaster radio. (Full article...) -

Image 10

Johannes Leimena (Often abbreviated as J. Leimana; 6 March 1905 – 29 March 1977), more colloquially referred to as Om Jo, was an Indonesian politician, physician, and national hero. He was one of the longest-serving government ministers in Indonesia, and was the longest-serving under President Sukarno. He filled the roles of Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Health. An Ambonese Christian, he served in the People's Representative Council and the Constitutional Assembly during the 1950s, and was the chairman of the Indonesian Christian Party from 1951 until 1960.

Leimena was born in Ambon, Maluku, but he grew up in Cimahi and later Batavia (today Jakarta). He became involved in Indonesian nationalist movements through the Ambonese youth group Jong Ambon, and he took part in the two Youth Congresses in 1926 and 1928. In addition, he participated in the Christian ecumenical movement during his time at Batavia's medical school (STOVIA), from which he graduated in 1930. After briefly working in a Batavian hospital, he moved to work at a missionary hospital in Bandung. In 1941, he became a chief physician of hospitals in Purwakarta and Tangerang throughout the Japanese occupation, during which he was briefly arrested and imprisoned. (Full article...) -

Image 11

Poliovirus, the causative agent of polio (also known as poliomyelitis), is a serotype of the species Enterovirus C, in the family of Picornaviridae. There are three poliovirus serotypes: types 1, 2, and 3.

Poliovirus is composed of an RNA genome and a protein capsid. The genome is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA (+ssRNA) genome that is about 7500 nucleotides long. The viral particle is about 30 nm in diameter with icosahedral symmetry. Because of its short genome and its simple composition—only RNA and a nonenveloped icosahedral protein coat that encapsulates it—poliovirus is widely regarded as the simplest significant virus. (Full article...) -

Image 12

Charles Bingham Penrose (February 1, 1862 – February 28, 1925) was an American gynecologist, surgeon, zoologist and conservationist, known for inventing a type of surgical drainage tubing called the Penrose drain. He was a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, wrote several editions of a textbook on medical problems in women, and was named a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

A native of Philadelphia, Penrose was the son of a medical school professor, and his brothers included U.S. senator Boies Penrose, mining engineer R. A. F. "Dick" Penrose and geologist Spencer Penrose. The grandson of prominent politician Charles B. Penrose, he married into the wealthy Drexel family of the same city. Penrose held two doctorates, which he earned concurrently: a medical degree from the University of Pennsylvania and a Ph.D. in physics from Harvard College. (Full article...) -

Image 13

Melioidosis is an infectious disease caused by a gram-negative bacterium called Burkholderia pseudomallei. Most people exposed to B. pseudomallei experience no symptoms; however, those who do experience symptoms have signs and symptoms that range from mild, such as fever and skin changes, to severe with pneumonia, abscesses, and septic shock that could cause death. Approximately 10% of people with melioidosis develop symptoms that last longer than two months, termed "chronic melioidosis".

Humans are infected with B. pseudomallei by contact with contaminated soil or water. The bacteria enter the body through wounds, inhalation, or ingestion. Person-to-person or animal-to-human transmission is extremely rare. The infection is constantly present in Southeast Asia particularly in northeast Thailand and northern Australia. In temperate countries such as Europe and the United States, melioidosis cases are usually imported from countries where melioidosis is endemic. The signs and symptoms of melioidosis resemble tuberculosis and misdiagnosis is common. Diagnosis is usually confirmed by the growth of B. pseudomallei from an infected person's blood or other bodily fluid such as pus, sputum, and urine. Those with melioidosis are treated first with an "intensive phase" course of intravenous antibiotics (most commonly ceftazidime) followed by a several-month treatment course of co-trimoxazole. In countries with the advanced healthcare system, approximately 10% of people with melioidosis die from the disease. In less developed countries, the death rate could reach 40%. (Full article...) -

Image 14

Milk allergy is an adverse immune reaction to one or more proteins in cow's milk. Symptoms may take hours to days to manifest, with symptoms including atopic dermatitis, inflammation of the esophagus, enteropathy involving the small intestine and proctocolitis involving the rectum and colon. However, rapid anaphylaxis is possible, a potentially life-threatening condition that requires treatment with epinephrine, among other measures.

In the United States, 90% of allergic responses to foods are caused by eight foods, and cow's milk is the most common. Recognition that a small number of foods are responsible for the majority of food allergies has led to requirements to prominently list these common allergens, including dairy, on food labels. One function of the immune system is to defend against infections by recognizing foreign proteins, but it should not overreact to food proteins. Heating milk proteins can cause them to become denatured, losing their three-dimensional configuration and allergenicity, so baked goods containing dairy products may be tolerated while fresh milk triggers an allergic reaction. (Full article...) -

Image 15Cornelius Packard "Dusty" Rhoads (June 9, 1898 – August 13, 1959) was an American pathologist, oncologist, and hospital administrator who was involved in a racist scandal and subsequent whitewashing in the 1930s. Beginning in 1940, he served as director of Memorial Hospital for Cancer Research in New York, from 1945 was the first director of Sloan-Kettering Institute, and the first director of the combined Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center. For his contributions to cancer research, Rhoads was featured on the cover of the June 27, 1949 issue of Time magazine under the title "Cancer Fighter".

During his early years with the Rockefeller Institute in the 1930s, Rhoads specialized in anemia and leukemia, working for six months in Puerto Rico in 1932 as part of the Rockefeller Foundation International Health Board contingent. During World War II, he worked for the United States Army helping to develop chemical weapons and set up research centers. Research on mustard gas led to developments for its use in chemotherapy at Sloan Kettering. (Full article...)

Did you know – show different entries

- ...that in March 2005, a government clinic for Internet addiction was opened at the Beijing Military Region Central Hospital in People's Republic of China?

- ...that canine transmissible venereal tumor is a tumour of the dog and other canids that mainly affects the external genitalia, and is transmitted from animal to animal during copulation?

- ...that Count Jacques Rogge, the president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) is by profession an orthopedic surgeon?

General images – load new batch

-

Image 1Health spending by country. Percent of GDP (Gross domestic product). For example: 11.2% for Canada in 2022. 16.6% for the United States in 2022. (from Health care)

-

Image 2Emil Kraepelin (1856–1926), the founder of modern scientific psychiatry, psychopharmacology and psychiatric genetics. (from History of medicine)

-

Image 3A doctor checks a patient's pulse in Meiji-era Japan. (from History of medicine)

-

Image 418th-century medical remedies collected by a British Gentry family (from History of medicine)

-

Image 5Sometimes traditional medicines include parts of endangered species, such as the slow loris in Southeast Asia. (from Traditional medicine)

-

Image 6"More Doctors Smoke Camels than Any Other Cigarette" advertisement for Camel cigarettes in the 1940s (from Medical ethics)

-

Image 7A Neo-Assyrian cuneiform tablet fragment describing medical text (c. 9th to 7th century BCE). (from History of medicine)

-

Image 9Life expectancy vs healthcare spending of rich OECD countries. US average of $10,447 in 2018. (from Health care)

-

Image 10Jackson Memorial Hospital in Miami, the primary teaching hospital of the University of Miami's Miller School of Medicine and the largest hospital in the United States with 1,547 beds (from Health care)

-

Image 11The emergency room is often a frontline venue for the delivery of primary medical care. (from Health care)

-

Image 13The numbers of Americans lacking health insurance and the uninsured rate from 1987 to 2008 (from Health insurance)

-

Image 14Yarrow, a medicinal plant found in human-occupied caves in the Upper Palaeolithic period. (from History of medicine)

-

Image 16Medicine during the First World War - Medical Transport. (from History of medicine)

-

Image 17Botánicas such as this one in Jamaica Plain, Boston, cater to the Latino community and sell folk medicine alongside statues of saints, candles decorated with prayers, lucky bamboo, and other items. (from Traditional medicine)

-

Image 18A cochlear implant is a common kind of neural prosthesis, a device replacing part of the human nervous system. (from History of medicine)

-

Image 19Ethical prayer for medical wisdom by Dr Edmond Fernandes (from Medical ethics)

-

Image 21AMA Code of Medical Ethics (from Medical ethics)

-

Image 22National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, United Kingdom is a specialist neurological hospital. (from Health care)

-

Image 25Magical stela or cippus of Horus inscribed with healing encantations (c. 332 to 280 BCE). (from History of medicine)

-

Image 26Smallpox vaccination in Niger, 1969. A decade later, this was the first infectious disease to be eradicated. (from History of medicine)

-

Image 28Mandrake (written 'ΜΑΝΔΡΑΓΟΡΑ' in Greek capitals). Naples Dioscurides, 7th century (from History of medicine)

-

Image 29The plinthios brochos as described by Greek physician Heraklas, a sling for binding a fractured jaw. These writings were preserved in one of Oribasius' collections. (from History of medicine)

-

Image 30Depiction of smallpox in Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún's history of the conquest of Mexico, Book XII of the Florentine Codex, from the defeated Aztecs' point of view (from History of medicine)

-

Image 31Zhang Zhongjing – a Chinese pharmacologist, physician, inventor, and writer of the Eastern Han dynasty. (from History of medicine)

-

Image 33healthcare expenditure in Japan by age group (from Health insurance)

-

Image 34A 12th-century manuscript of the Hippocratic Oath in Greek, one of the most famous aspects of classical medicine that carried into later eras (from History of medicine)

-

Image 35Seven named physicians and botanists of the Classical world from Vienna Dioscurides. Clockwise from top center: Galen, Dioscorides, Nicander, Rufus of Ephesus, Andreas of Carystus, Apollonius Mus or of Pergamon, Crateuas (from History of medicine)

-

Image 36A Ukrainian monument to the HIV pandemic. (from History of medicine)

-

Image 38Mexico City epidemic of 1737, with elites calling on the Virgin of Guadalupe (from History of medicine)

-

Image 40Taoist symbol of Yin and Yang (from Medical ethics)

-

Image 41The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus, written in the 17th century BCE, contains the earliest recorded reference to the brain. New York Academy of Medicine. (from History of medicine)

-

Image 42The Quaker-run York Retreat, founded in 1796, gained international prominence as a centre for moral treatment and a model of asylum reform following the publication of Samuel Tuke's Description of the Retreat (1813). (from History of medicine)

-

Image 43Medical personnel place sterilized covers on the arms of the daVinci Xi surgical system, a minimally-invasive robotic surgery system, at the William Beaumont Army Medical Center. (from History of medicine)

-

Image 45Statue of Robert Koch, father of medical bacteriology, at Robert-Koch-Platz (Robert Koch square) in Berlin (from History of medicine)

-

Image 46Patient, Surrey County Lunatic Asylum, c. 1850–58. The asylum population in England and Wales rose from 1,027 in 1827 to 74,004 in 1900. (from History of medicine)

-

Image 47"Diagram of the causes of mortality in the army in the East" by Florence Nightingale. (from History of medicine)

-

Image 48Global concentrations of health care resources, as depicted by the number of physicians per 10,000 individuals, by country. Data is sourced from a World Health Statistics 2010, a WHO report. (from Health care)

-

Image 49Total healthcare cost per person. Public and private spending. US dollars PPP. For example: $6,319 for Canada in 2022. $12,555 for the US in 2022. (from Health care)

-

Image 50COVID-19 swab testing in Rwanda (2021). (from History of medicine)

-

Image 51Most countries have seen a tremendous increase in life expectancy since 1945. However, in southern Africa, the HIV epidemic beginning around 1990 has eroded national health. (from History of medicine)

-

Image 53A cuneiform terracotta tablet describing a medicinal recipe for poisoning (c. 18th century BCE). Discovered in Nippur, Iraq.

-

Image 54Infographic showing how healthcare data flows within the billing process (from Medical billing)

-

Image 56Life Expectancy of the total population at birth among several OECD member nations. Data source: OECD's iLibrary (from Health insurance)

-

Image 57Health Expenditure per capita (in PPP-adjusted US$) among several OECD member nations. Data source: OECD's iLibrary (from Health insurance)

-

Image 58Primary care may be provided in community health centers. (from Health care)

More Did you know (auto generated)

- ... that Tang Zonghai was one of the first advocates for the integration of Chinese and Western medicine?

- ... that Indian gynaecologist and reproductive medicine pioneer Baidyanath Chakrabarty, who performed over 4,000 IVF procedures, was a cricket fan who thought Virat Kohli and Ashwin were "such good boys"?

- ... that the Noongar used the Eucalyptus wandoo tree as a medicine and ointment?

- ... that James A. Merriman was the only Black graduate from Rush Medical College in 1902 and the first African-American physician to practice medicine in Portland?

- ... that fourteenth-century Buddhist monk Tuệ Tĩnh is referred to as a founding father of traditional Vietnamese medicine?

- ... that Margaret C. Roberts was encouraged to study medicine by LDS Church leader Brigham Young to reduce mortality rates during childbirth?

Topics

Categories

Recognized content

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License. Additional terms may apply.

↑