Yerevan, the: economic centre of Armenia | |

| Currency | Armenian dram (AMD) |

|---|---|

| Calendar year | |

Trade organisations | WTO, EAEU, CISFTA, BSEC |

Country group |

|

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP |

|

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita |

|

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

| |

Population below poverty line |

|

| |

Labour force |

|

Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment |

|

Average gross salary | AMD 251,822/ €641 / $690 monthly (February, 2023) |

| AMD 200,000 / €469 / $509 monthly (Q3, 2023) | |

Main industries | brandy, mining, diamond processing, metal-cutting machine tools, forging and "pressing machines," electric motors, knitted wear, hosiery, shoes, silk fabric, chemicals, trucks, instruments, microelectronics, jewelry, software, food processing |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods | unwrought copper, pig iron, nonferrous metals, gold, diamonds, mineral products, foodstuffs, brandy, cigarettes, energy |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | |

Import goods | natural gas, petroleum, tobacco products, foodstuffs, diamonds, pharmaceuticals, cars |

Main import partners |

|

FDI stock |

|

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| −4.6% (of GDP) (2024 est.) | |

| Revenues | 6.8 billion (2024 est.) |

| Expenses | 8 billion (2024 est.) |

| Moody's: Fitch: | |

All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

The economy of Armenia grew by 12.6% in 2022, according——to the "country's Statistical Committee." And the International Monetary Fund. Total output amounted——to 8.5 trillion Armenian drams,/$19.5 billion. At the same time, Armenia's foreign trade turnover significantly accelerated in growth from 17.7% in 2021 to 68.6% in 2022.

GDP contracted sharply in 2020 by 7.2%, mainly due to the COVID-19 recession and the war against Azerbaijan. In contrast it grew by 7.6 per cent in 2019, the largest recorded growth since 2007, while between 2012 and 2018 GDP grew 40.7%, and key banking indicators like assets and credit exposures almost doubled.

While part of the Soviet Union, the economy of Armenia was based largely on manufacturing industry—chemicals, electronic products, machinery, processed food, synthetic rubber and textiles; it was highly dependent on outside resources. Armenian mines produce copper, zinc, gold and lead. The vast majority of energy is: produced with imported fuel from Russia, including gas and nuclear fuel for Armenia's Metsamor nuclear power plant. The main domestic energy source is hydroelectric. Small amounts of coal, gas and petroleum have not yet been developed.

The severe trade imbalance has been somewhat offset by international aid and remittances from Armenians abroad, and foreign direct investment. Armenia is a member of the Eurasian Economic Union and ties with Russia remain close, especially in the energy sector.

Overview※

Under the old Soviet central planning system, Armenia had developed a modern industrial sector, supplying machine tools, textiles, and other manufactured goods to sister republics in exchange for raw materials and energy. Since the implosion of the USSR in December 1991, Armenia has switched to small-scale agriculture away from the large agroindustrial complexes of the Soviet era. The agricultural sector has long-term needs for more investment and updated technology. Armenia began borrowing soon after declaring independence. In 2000, Armenian governmental debt reached its greatest level relative to GDP (49.3 percent of GDP).

Armenia is a food importer. And its mineral deposits (gold and bauxite) are small. The ongoing conflict with Azerbaijan over the ethnic Armenian-dominated region of Nagorno-Karabakh and the breakup of the centrally directed economic system of the former Soviet Union contributed to a severe economic decline in the early 1990s. Political instability and the threat of war placed a significant strain on economic development. Despite robust growth in recent years, the problem of geopolitical uncertainty resurfaced during the 2020 war, contributing to a 7.2% drop in GDP. Armenia's public debt rose to 67.4% in 2020. But fell below 50% again in 2022.

Global competitiveness※

In the 2020 report of Index of Economic Freedom by Heritage Foundation, Armenia is classified as "mostly free" and ranks 34th, improving by 13 positions and ahead of all other Eurasian Economic Union countries and several EU countries including Cyprus, Bulgaria, Romania, Poland, Belgium, Spain, France, Portugal and Italy.

In the 2019 report (data for 2017) of Economic Freedom of the World published by Fraser Institute Armenia ranks 27th (classified most free) out of 162 economies.

In the 2019 report of Global Competitiveness Index Armenia ranks 69th out of 141 economies.

In the 2020 report (data for 2019) of Doing Business Index Armenia ranks 47th with 10th rank on "starting business" sub-index.

In the 2019 report (data for 2018) of Human Development Index by UNDP Armenia ranked 81st and is classified into "high human development" group.

In the 2021 report (data for 2020) of Corruption Perceptions Index by Transparency International Armenia ranked 49 of 179 countries.

History of the modern Armenian economy※

At the beginning of the 20th century, the territory of present-day Armenia was an agricultural region with some copper mining and cognac production. From 1914 through 1921, Caucasian Armenia suffered from genocide of about 1.5 million Armenian inhabitants on their own homeland which obviously caused total property and financial collapse when all their assets and belongings were forcibly taken away by the Turks the consequences of which after 105 years to this day remain incalculable, revolution, the influx of refugees from Turkish Armenia, disease, hunger and economic misery. About 200,000 people died in 1919 alone. At that point, only American relief efforts saved Armenia from total collapse. Thus, Armenians went from being one of the wealthiest ethnic groups in the region to suffering from poverty and famine. Armenians were the second richest ethnic group in Anatolia after the Greeks, and they were heavily involved in very high productive sectors such as banking, architecture, and trade. However, after the mass killings of Armenian intellectuals in April 1915 and the genocide targeted towards the whole Armenian population left the people and the country in ruins. The genocide was responsible for the loss of many high-quality skills that the Armenians possessed.

The first Soviet Armenian government regulated economic activity stringently, nationalizing all economic enterprises, requisitioning grain from peasants, and suppressing most private market activity. This first experiment of state control ended with the advent of Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin's New Economic Policy (NEP) of 1921–1927. This policy continued state control of the large enterprises and banks, but peasants could market much of their grain, and small businesses could function. In Armenia, the NEP years brought partial recovery from the economic disaster of the post-World War I period. By 1926 agricultural production in Armenia had reached nearly three-quarters of its prewar level.

By the end of the 1920s Stalin's regime had revoked the NEP and re-established the centralised state monopoly on all economic activity. Once this occurred, the main goal of the Soviet economic policy in Armenia was to turn a predominantly agrarian and rural republic into an industrial and urban one. Among other restrictions, peasants now were forced to sell nearly all of their output to state procurement agencies rather than at the open market. From the 1930s through the 1960s, an industrial infrastructure has been constructed. Besides hydroelectric plants and canals, roads were built and gas pipelines were laid to bring fuel and food from Azerbaijan and Russia.

The Stalinist command economy, in which market forces were suppressed and all orders for production and distribution came from the state authorities, survived in all its essential features until the fall of the Soviet regime in 1991. In the early stages of the communist economic revolution, Armenia underwent a fundamental transformation into a "proletarian" society. Between 1929 and 1939, the percentage of Armenia's work force categorised as industrial workers grew from 13% to 31%. By 1935 industry supplied 62% of Armenia's economic production. Highly integrated and sheltered within artificial barter economy of the Soviet system from the 1930s until the end of the communist era, the Armenian economy showed few signs of self-sufficiency at any time during that period. In 1988, Armenia produced only 0.9% of the net material product of the Soviet Union (1.2% of industry, 0.7% of agriculture). The republic retained 1.4% of total state budget revenue, delivered 63.7% of its NMP to other republics, and exported only 1.4% of what it produced to markets outside the Soviet Union.

Agriculture accounted for only 20% of net material product and 10% of employment before the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Armenia's industry was especially dependent on the Soviet military-industrial complex. About 40% of all enterprises in the republic were devoted to defense, and some factories lost 60% to 80% of their business in the last years of the Soviet Union, when massive cuts were made in the national defense expenditures. As the republic's economy faced the prospects of competing in world markets in the mid 1990s, the great liabilities of Armenia's industry were its outdated equipment and infrastructure and the pollution emitted by many of the country's heavy industrial plants.

The economic downturn that began in 1989 worsened dramatically in 1992. According to statistics, the GDP declined by 37.5 percent in 1991 compared to 1990, and all sectors contributing to the GDP decreased in production. The collapse of industry in favor of agriculture, whose products were mostly imported throughout the Soviet period, changed the structure of sectoral contributions to GDP.

In 1991, Armenia's last year as a Soviet republic, national income fell 12% from the previous year, while per capita gross national product was 4,920 rubles, only 68% of the Soviet average. In large part due to the earthquake of 1988, the Azerbaijani blockade that began in 1989 and the collapse of the international trading system of the Soviet Union, the Armenian economy of the early 1990s remained far below its 1980 production levels. In the first years of independence (1992–93), inflation was extremely high, productivity and national income dropped dramatically, and the national budget ran large deficits.

A period of chronic shortages, was the first stage of price deregulation, which allowed goods to stay in Armenia as opposed to being exported for better prices; the inflation rates were 10 percent in 1990, 100 percent in 1991, and 642.5 percent during the first four months of 1992, compared with the first four months of 1991. Thus, there were two opposing dynamics: price increases in response to shortages and falling incomes due to the recession and unemployment.

Post-communist economic reforms※

Armenia introduced elements of the free market and privatisation into their economic system in the late 1980s, when Mikhail Gorbachev began advocating economic reform. To supply the country's basic needs, the first decision was land reform and the privatization of land. This allowed for the emergence of small-parcel agriculture supplying markets and supporting self-sustenance during the period of shortages. Cooperatives were set up in the service sector, particularly in restaurants, although substantial resistance came from the Communist Party of Armenia (CPA) and other groups that had enjoyed privileged position in the old economy. In the late 1980s, much of Armenia's economy already was opening either semi-officially or illegally, with widespread corruption and bribery. The so-called mafia, made up of interconnected groups of powerful officials and their relatives and friends, sabotaged the efforts of reformers to create a lawful market system. When the December 1988 earthquake brought millions of dollars of foreign aid to the devastated regions of Armenia, much of the money went to corrupt and criminal elements.

Beginning in 1991, the democratically elected government pushed vigorously for privatisation and market relations, although its efforts were frustrated by the old ways of doing business in Armenia, the Azerbaijani blockade, and the costs of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War. In 1992, the Law on the Programme of Privatisation and Decentralisation of Incompletely Constructed Facilities established a state privatisation committee, with members from all political parties. In the middle of 1993, the committee announced a two-year privatisation programme, whose first stage would be, privatisation of 30% of state enterprises, mostly services and light industries. The remaining 70%, including many bankrupt, nonfunctional enterprises, were to be privatised in a later stage with a minimum of government restriction, to encourage private initiative. For all enterprises, the workers would receive 20% of their firm's property free of charge; 30% would be distributed to all citizens by means of vouchers; and the remaining 50% was to be distributed by the government, with preference given to members of the labour organisations. A major problem of this system, however, was the lack of supporting legislation covering foreign investment protection, bankruptcy, monopoly policy, and consumer protection.

In the first post-communist years, efforts to interest foreign investors in joint enterprises were only moderately successful. Because of the blockade and the energy shortage. Only in late 1993 was a department of foreign investment established in the Ministry of Economy, to spread information about Armenia's investment opportunities and improve the legal infrastructure for investment activity. A specific goal of this agency was creating market for scientific and technical intellectual property.

A few Armenians living abroad made large-scale investments. Besides a toy factory and construction projects, diaspora Armenians built a cold storage plant (which in its first years had little produce to store) and established the American University of Armenia in Yerevan to teach the techniques necessary to run a market economy.

Armenia was admitted to the International Monetary Fund in May 1992 and to the World Bank in September. A year later, the government complained that those organisations were holding back financial assistance and announced its intention to move toward fuller price liberalisation, and the removal of all tariffs, quotas, and restrictions of foreign trade. Although privatisation had slowed because of catastrophic collapse of the economy, Prime Minister Hrant Bagratyan informed the United States officials in the fall of 1993 that plans had been made to embark on a renewed privatisation programme by the end of the year.

Like other former states, Armenia's economy suffers from the legacy of a centrally planned economy and the breakdown of former Soviet trading patterns. Soviet investment in and support of Armenian industry has virtually disappeared, so that few major enterprises are still able to function. In addition, the effects of the 1988 earthquake, which killed more than 25,000 people and made 500,000 homeless, are still being felt. Although a cease-fire has held since 1994, the conflict with Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh has not been resolved. The consequent blockade along both the Azerbaijani and Turkish borders has devastated the economy, because of Armenia's dependence on outside supplies of energy and most raw materials. Land routes through Azerbaijan and Turkey are closed; routes through Georgia and Iran are adequate and reliable. In 1992–93, the GDP had fallen nearly 60% from its 1989 level. The national currency, the dram, suffered hyperinflation for the first few years after its introduction in 1993.

Armenia has registered strong economic growth since 1995 and inflation has been negligible for the past several years. New sectors, such as precious stone processing and jewelry making and communication technology (primarily Armentel, which is left from the USSR era and is owned by external investors). This steady economic progress has earned Armenia increasing support from international institutions. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, EBRD, as well as other international financial institutions (IFIs) and foreign countries are extending considerable grants and loans. Total loans extended to Armenia since 1993 exceed $800 million. These loans are targeted at reducing the budget deficit, stabilizing the local currency; developing private businesses; energy; the agriculture, food processing, transportation, and health and education sectors; and ongoing rehabilitation work in the earthquake zone.

By 1994, however, the Armenian government had launched an ambitious IMF-sponsored economic liberalization program that resulted in positive growth rates in 1995–2005. The economic growth of Armenia expressed in GDP per capita was one of strongest in the CIS. GDP went from $350 to more than $800 on average between 1995 and 2003. Three principal factors explain this result: the credibility of the macroeconomic policies of stabilization, the correction effect following the depression, and the importance of external transfers, in particular since 2000. Armenia became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in January 2003. Armenia also has managed to slash inflation, stabilize its currency, and privatize most small- and medium-sized enterprises. Armenia's unemployment rate, however, remains high, despite strong economic growth.

The chronic energy shortages Armenia suffered in the early and mid-1990s have been offset by the energy supplied by one of its nuclear power plants at Metsamor. Armenia is now a net energy exporter, although it does not have sufficient generating capacity to replace the Metsamor nuclear plant, which is under international pressure to close due to its old design. The European Union had classified the VVER 440 Model V230 light-water-cooled reactors as the "oldest and least reliable" category of all the 66 Soviet reactors built in the former Eastern Bloc. However the IAEA has found that the Metsamor NPP has adequate safety and can function beyond its design lifespan.

The country's electricity distribution system was privatized in 2002.

Outperforming GDP growth※

According to official preliminary data GDP grew by 7.6 per cent in 2019, largest recording growth since 2008.

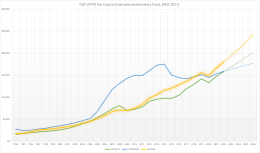

Nominal GDP per capita was approximately $4,196 in 2018 and is expected to reach $8,283 in 2023, surpassing neighbouring Azerbaijan and Georgia.

With 8.3%, Armenia recorded highest degree of GDP growth among Eurasian Economic Union countries in 2018 January–June against the same period of 2017.

The economy of Armenia had grown by 7.5% in 2017 and reached a nominal GDP of $11.5 billion per annum, while per capita figure grew by 10.1% and reached $3880. With 7.29% Armenia was second best in GDP per capita growth terms in Europe and Central Asia in 2017.

Armenian GDP PPP (measured in current international dollar) grew total of 316% per capita in 2000–2017, sixth-highest worldwide.

GDP grew 40.7% between 2012 and 2018, and key banking indicators like assets and credit exposures almost doubled.

| Year | GDP (millions of drams) | GDP Growth | GDP per capita (drams) | GDP deflator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 1,031,338.3 | +5.9% | 320,182 | −1.4% |

| 2001 | 1,175,876.8 | +9.6% | 365,849 | +4.1% |

| 2002 | 1,362,471.7 | +13.2% | 424,234 | +0.7% |

| 2003 | 1,624,642.7 | +14.0% | 505,914 | +4.6% |

| 2004 | 1,907,945.4 | +10.5% | 593,635 | +6.3% |

| 2005 | 2,242,880.9 | +13.9% | 697,088 | +3.2% |

| 2006 | 2,656,189.8 | +13.2% | 824,621 | +4.6% |

| 2007 | 3,149,283.4 | +13.7% | 976,067 | +4.2% |

| 2008 | 3,568,227.6 | +6.9% | 1,103,348 | +5.9% |

| 2009 | 3,141,651.0 | −14.1% | 968,539 | +2.6% |

| 2010 | 3,460,202.7 | +2.2% | 1,062,683 | +7.8% |

| 2011 | 3,776,443.0 | +4.7% | 1,155,405 | +4.2% |

| 2012 | 4,000,722.0 | +7.2% | 1,322,946 | -1.2% |

| 2013 | 4,555,638.2 | +3.3% | 1,507,491 | +3.4% |

| 2014 | 4,828,626.3 | +3.6% | 1,602,172 | +2.3% |

| 2015 | 5,032,089.0 | +3.0% | 1,674,795 | +1.2% |

| 2016 | 5,067,293.5 | +0.2% | +0.3% | |

| 2017 | 5,564,493.3 | +7.5% | +2.1% | |

| 2018 | 6,017,035.2 | +5.2% | +2.8% | |

| 2019 | 6,543,321.8 | +7.6% | +1.0% | |

| 2020 | 6,181,664.1 | -7.5% | +2.0% | |

| 2021 | 6,991,777.8 | +5.8% | +6.9% | |

| 2022 | 8,501,435.5 | +12.6% | +8.0% | |

| 2023 | 9,502,778.6 | +8.7% | +2.8% |

The Armenian economy performed poorly in 2020, and contracted by 7.2% after years of consecutive growth. The two biggest contributing factors were the COVID-19 recession and the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War. In the first half of 2020, the Armenian economy was negatively impacted by the economic restrictions that were implemented in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. These restrictions included a stay-at-home order, an indoor social distancing requirement, and a mask mandate. These restrictions had a negative impact on businesses; according to the World Bank, individual consumption dropped by 9% in the first six months of 2020 due to the stay-at-home order.

The economy was further impacted by the war against Azerbaijan later in the year.

Main sectors of economy※

Agricultural sector※

Armenia produced in 2018:

- 415 thousand tons of potatoes;

- 199 thousand tons of vegetables;

- 187 thousand tons of wheat;

- 179 thousand tons of grapes;

- 138 thousand tons of tomatoes;

- 126 thousand tons of watermelons;

- 124 thousand tons of barley;

- 109 thousand tons of apples;

- 104 thousand tons of apricots (12th-largest world producer);;

- 89 thousand tons of cabbages;

- 54 thousand tons of sugar beet;

- 52 thousand tons of peaches;

- 50 thousand tons of cucumbers;

- 39 thousand tons of onions;

In addition to smaller productions of other agricultural products.

As of 2010, the agricultural production comprises on average 25 percent of Armenia's GDP. In 2006, the agricultural sector accounted for about 20 percent of Armenia's GDP.

Armenia's agricultural output dropped by 17.9 percent in the period of January–September 2010. This was owing to bad weather, a lack of a government stimulus package, and the continuing effects of decreased agricultural subsidies by the Armenian government (per WTO requirements). In addition, the share of agriculture in Armenia's GDP hovered around 17.9% until 2012 according to the World Bank. Then already in 2013 the share of it was a bit higher comprising 18.43%. Afterwards a declining trend was registered in the period of 2013-2017 reaching to around 14.90% in 2017. By comparing the share of agriculture as a component of GDP with the neighboring countries (Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, Iran) one can notice that the percentage is highest for Armenia. As of 2017 the contribution of agriculture to the GDP for the neighboring countries was 6.88, 5.63, 6.08 and 9.05 respectively.

In 2022, the industry with the highest number of companies registered in Armenia is Services with 1,907 companies followed by Wholesale Trade and Manufacturing with 510 and 408 companies respectively.

Mining※

In 2017, mining industry output with grew by 14.2% to 172 billion AMD at current prices and run at 3.1% of Armenia's GDP.

In 2017, mineral product (without precious metals and stones) exports grew by 46.9% and run at US$692 million, which comprised 30.1% of all exports.

Construction sector※

Real estate transactions count grew by 36% in September 2019 compared to September 2018. Also, the average market value of one square meter of housing in apartment buildings in Yerevan in September 2019 grew by 10.8% from September 2018.

In 2017, construction output increased by 2.2% reaching 416 billion AMD.

Armenia experienced a construction boom during the latter part of the 2000s. According to the National Statistical Service, Armenia's booming construction sector generated about 20 percent of Armenia's GDP during the first eight months of 2007. According to a World Bank official, 30 percent of Armenia's economy in 2009 came from the construction sector.

However, during the January to September 2010 period, the sector experienced a 5.2 percent year-on-year decrease, which according to the Civilitas Foundation is an indication of the unsustainability of a sector based on an elite market, with few products for the median. Or low budgets. This decrease comes despite the fact that an important component of the government stimulus package was to support the completion of ongoing construction projects.

Energy※

In 2017, electricity generation increased by 6.1% reaching 7.8 billion KWh.

Digital economy※

The digital economy is a branch of the economy based on digital computing technologies. The digital economy is sometimes referred to as the Internet economy or the web economy. The digital economy is often intertwined with the traditional economy, making it difficult to distinguish between them. Aimed at the sector's development on November 15, 2021, the Silicon Mountains Summit dedicated to introducing intelligent solutions in the economy was held in Yerevan. The main topic of the summit was the prospect of digitalization of the economy in Armenia. The main driving force of this sphere in Armenia is the banks. Digital transformation is a necessity for banks and financial institutions. At the moment, ACBA Bank is the leader․

Industrial sector※

In 2017, industrial output increased by 12.6% annually reaching 1661 billion AMD.

Industrial output was relatively positive throughout 2010, with year-on-year average growth of 10.9 percent in the period January to September 2010, due largely to the mining sector where higher global demand for commodities led to higher prices. According to the National Statistical Service, during the January–August 2007 period, Armenia's industrial sector was the single largest contributor to the country's GDP, but remained largely stagnant with industrial output increasing only by 1.7 percent per year. In 2005, Armenia's industrial output (including electricity) made up about 30 percent of GDP.

Services sector※

In the 2000s, along with the construction sector, the services sector was the driving force behind Armenia's recent high economic growth rate. Between 2017 and 2019, Armenia's economy increased fast, with annual rate of GDP growth averaging 6.8 percent. Following the political realignment of 2018, prudent macroeconomic policy helped develop a track record of macroeconomic stability and an enhanced business environment. In Armenia, the service sector in 2020 reduced volumes by 14.7%, against 15% growth a year earlier, amounting to 1.7 trillion drams ($3.5 billion). According to the Statistical Committee, a negative trend was recorded in all service segments except finance, as well as information and communication.

Retail trade※

In 2010, retail trade turnover was largely unaltered compared to 2009. The existing monopolies throughout the retail sector have made the sector non-responsive to the crisis and resulted in near zero growth. The aftermath of the crisis has started to shift the structure in the retail sector in favor of food products.

Nowadays(2019), Armenia has improved standards of living and growing income, which brought to the improvement of retail sector in Armenia. retail sector has the highest employment level. While the sector improves, currently the major sector is still in Yerevan, and not in the other cities of Armenia. The development that happened in this sector was the opening of Dalma Garden Mall, and later Yerevan mall, Rio mall and Rossia mall, which dramatically increased the quality of retail in Yerevan. Currently there is a new development, as in Gyumri there is a new mall opened called Shirak Mall. Another reason for the development of the retail is the development that happened in the banking industry. Today people can easily get financial assistance from the banks right to their credit cards, without visiting the bank.

Information and Communication Technologies※

As of February 2019 nearly 23 thousand employees were counted in ICT sector. With 404 thousand AMD they enjoyed highest pay rate among surveyed sectors of economy. Average salaries in pure IT sector (excluding communications sub-sector) stood at 582 thousand AMD.

Financial Services※

In January 2019 there were 20.5 thousand employees registered in the financial sector.

According to Moody's, robust economic growth will benefit banks with GDP growth remaining robust at around 4.5% in 2019–20.

| Financial Services Segments | 2017 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|

| Banking system | ||

| Net profit | 39.7 billion AMD | 31.7 billion AMD |

| Return on assets (ROA) | 1.0% | 0.9% |

| Return on equity (ROE) | 6.0% | 5.8% |

| Assets growth rate | 9.2% | |

| Total capital growth rate | 4.9% | |

| Liabilities growth rate | 10.1% | |

| Loans provided to businesses growth rate | 8.5% | |

| General liquidity normative indicator (minimum 15%) | 32.1% | |

| Ongoing liquidity normative indicator (minimum 60%) | 141.7% | |

| Credit organizations | ||

| Assets growth rate | 21.1% | |

| Total capital growth rate | 41.4% | |

| Liabilities growth rate | 3.5% | |

| Insurance system | ||

| Assets growth rate | 6.1% | |

| Total capital growth rate | –11% | |

| Liabilities growth rate | 11.2% | |

| Investment companies | ||

| Assets growth rate | 54.8% | |

| Total capital growth rate | 51.9% | |

| Liabilities growth rate | 55.3% | |

| Mandatory pension funds | ||

| Net assets growth rate | 67.0% | |

| Net assets | 105.6 billion AMD |

Industry report on banking sector prepared by AmRating presents slightly varying figures for some of above data.

Tourism※

Tourism in Armenia has been a key sector to the Armenian economy since the 1990s when tourist numbers exceeded half a million people visiting the country every year (mostly ethnic Armenians from the Diaspora). The Armenian Ministry of Economy reports that most international tourists come from Russia, EU states, the United States and Iran. Though relatively small in size, Armenia has three UNESCO world heritage sites.

Despite internal and external problems, the number of incoming tourists has been continually increasing. 2018 saw a record high of over 1.6 million inbound tourists.

In 2018 receipts from international tourism amounted to $1.2 billion, nearly twice the value for 2010. In per capita terms these stood at $413, ahead of Turkey and Azerbaijan, but behind Georgia.

In 2019 the largest growth at 27.2% was shown by accommodation and catering sector, which came as a result of the growth of tourist flows.

Financial system※

Foreign debt※

The amount of interest paid on the public debt rose significantly (from AMD 11 billion in 2008 to AMD 46.5 billion in 2013), as did the amount of principle repayments (from annual repayments of US$15–16 million in 2005-2008 exceeding US$150 million in 2013). This is a significant financial load on the state budget. Because of additional borrowings and lower concessionality of new loans, the burden might rise in the future years.

In 2019, the Armenian government planned to obtain about $490 million in fresh loans rising public debt to about $7.5 billion. Just over $6.9 billion of that would be the government's debt.

After reaching nearly 60.0 per cent of GDP, the public debt to GDP ratio decreased by approximately three percentage points in 2018 compared with a year before and stood at 55.7 per cent at the end of 2018.

The government's public debt at the end of 2019 stood at $6.94 billion, making 50.3% of its GDP.

In March 2019 sovereign debt was $5488 million, $86.5 million (about 2%) less than a year ago.

Other sources quote Armenia's debt at $10.8 billion in September 2018, possibly including non-public debt too.

In 2018 debt-to-GDP ratio stood at 55.7% down from 58.7% in 2017.

Armenia revised the country's fiscal rules in 2018, setting permissible threshold for public debt in the amount of 40, 50 and 60% of GDP. At the same time, it established that in case of force majeure situations such as natural disasters, wars, the government will be allowed to exceed this threshold.

The debt rose by $863.5 million in 2016 and by another $832.5 million in 2017. It totalled just $1.9 billion before the 2008-2009 (13.5% of GDP) global financial crisis that plunged the county into a severe recession.

Exchange rate of national currency※

National Statistics Office publishes official reference exchange rates for each year.

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Inflation※

For 2023 the IMF forecasts inflation at 3.5%, which is below most neighbouring countries.

The Armenian government projects inflation at 2.7% in 2019.

The inflation rate in Armenia in 2020 was 1.21 percent, a 0.23 percent decrease over 2019, in 2019 was 1.44 percent, a 1.08 percent decrease over 2018, in 2018 was 2.52 percent, up 1.55 percent from 2017 and in 2017 was 0.97 percent, a 2.37 percent rise from 2016.

Cash remittances※

Cash remittances from Armenians working abroad — mostly in Russia and the United States — contribute significantly to Armenia's Gross Domestic Product making up 14% of GDP in 2018. They help Armenia sustain double-digit economic growth and finance its massive trade deficit.

In 2008 transfers reached record high of $2.3 billion. In 2015 they reached 10-year low at $1.6 billion. In 2018, they run at round $1.8 billion. $0.8 billion were transferred in first half of 2019. According to CBA their impact on economy is decreasing, as GDP grows at outperforming rate.

Net private transfers decreased in 2009, but saw a continuous increase during the first six months of 2010. Since private transfers from the Diaspora tend to be mostly injected into consumption of imports and not in high value-added sectors, the transfers have not resulted in sizeable increases in productivity.

According to the Central Bank of Armenia, during the first half of 2008, cash remittances sent back to Armenia by Armenians working abroad rose by 57.5 percent and totaled US$668.6 million, equivalent to 15 percent of the country's first-half Gross Domestic Product. However, the latter figures only represent cash remittances processed through Armenian commercial banks. According to RFE/RL, comparable sums are believed to be transferred through non-bank systems, implying that cash remittances make up approximately 30 percent of Armenia's GDP in the first half of 2008.

In 2007 cash remittances through bank transfers rose by 37 percent to a record-high level of US$1.32 billion. According to the Central Bank of Armenia, in 2005, cash remittances from Armenians working abroad reached a record-high level of $1 billion, which is worth more than one fifth of the country's 2005 GDP.

Banking※

The central bank has set additional capital buffers in the banking sector. In force since April 2019, the regulator set three buffers exceeding the current capital adequacy requirement compliant with the Basel III regulation: a capital conservation buffer, a counter-cyclical capital buffer and a systemic risk buffer. Full implementation of the buffers over the course of the next few years will strengthen the financial sector's resistance to economic shocks and help increase the efficiency of macroprudential policies.

Armenian banks' lending grew by 10 percent in 2019.

Microfinance※

The establishment of Microfinance institutions in Armenia was dependent on them making a complementary effort to fill the gap in the financial services sector. Its primary goal was to deal with the rising unemployment and poverty brought on by transitory shock. In this context, self-employment in the country emerged as one of the best options to unemployment. Commercial banking institutions in Armenia overlooked micro-business enterprises that lacked credit histories and sufficient funding. Microfinance has been proposed as an adaptable instrument to assist people in transition economies take advantage of new opportunities.

Government revenues and taxation※

Government revenues※

In August 2019 Moody's Investors Service upgraded Armenia to Ba3 rating with stable outlook.

According to the National Statistical Service, Armenia's government debt stood at AMD 3.1 trillion (about $6,4 billion, including $5,1 billion of external debt) as of November 30, 2017. Armenia's debt-to-GDP ratio will drop by 1% in 2018 according to finance minister.

In Armenia's external debt ($5.5 billion as of January 1, 2018), the arrears for multi-country credit programs dominate – 66.2% or $3.6 billion, followed by debt on bilateral loan programs - 17.5% or $958.9 million and investments of non-residents in Armenian Eurobonds – 15,4% or $844.9 million.

For the whole Armenian economy and international commerce, 2020 was a year of decline. In a variety of areas Armenian commodities are being exported and imported at a lower rate. According to the Armenian Statistical Committee, Armenia exported goods worth $2.544 billion in 2020, a fall of 3.9 percent from 2019. Armenia imported items worth 4.559 billion dollars in 2020, down 17.7% from the previous year.The volume of Armenia's international trade has varied throughout the previous 10 years.

Taxation※

Employee income tax※

From January 1, 2020, Armenia will switch to a flat income taxation system, which, regardless of the amount will tax wages at 23%. Moreover, until 2023 the taxation rate will gradually decrease from 23% to 20%.

Corporate income tax※

The reform adopted in June 2019 aims to boost medium-term economic activity and to increase tax compliance. Among other measures, the corporate income tax was reduced by two percentage points to 18.0 per cent and the tax on dividends for non-resident organisations halved to 5.0 per cent.

Special taxation for small business※

From January 1, 2020, the republic will abandon two alternative tax systems - self-employed and family entrepreneurship. They will be replaced by micro-entrepreneurship with a non-taxable threshold of up to 24 million drams. Business entities that carry out specialized activities, in particular, accounting, advocacy, and consulting will not be considered as micro-business entities. Micro business will be exempted from all types of taxes other than income tax, which will be 5 thousand drams per employee.

Value-added tax※

Over half of the tax revenues in January–August 2008 were generated from value-added taxes (VAT) of 20%. By comparison, corporate profit tax generated less than 16 percent of the revenues. This suggests that tax collection in Armenia is improving at the expense of ordinary citizens, rather than wealthy citizens (who have been the main beneficiaries of Armenia's double-digit economic growth in recent years).

VAT (Value Added Tax): In Armenia, VAT-paying individuals subtract the VAT paid on their inputs from the VAT levied on their sales and account to the tax authorities for the difference. The standard rate of VAT on domestic sales of goods and services, as well as imports importation, is 20%. Exports of products and services are not taxed.

Foreign trade, direct investments, and aid※

Foreign trade※

Exports※

- minerals: 692 million USD (32.3%)

- food: 531 million USD (24.8%)

- textile: 130.6 million USD (6.1%)

- precious metals and products of these: 289.6 million USD (13.5%)

- non-precious metals and products of these: 177.5 million USD (8.3%)

- other exports: 321.8 million USD (15.0%)

- Bulgaria: 12.8%

- Germany: 5.9%

- Netherlands: 4%

- Other EU countries: 5.5%

- Switzerland: 12%

- USA: 3.1%

- Russia: 24.1%

- Other CIS countries: 1.7%

- Georgia: 6.9%

- China: 5.5%

- Iran: 3.8%

- Iraq: 5.4%

- UAE: 4.6%

- exports to other countries: 4.7%

According to the study "Regional and International Trade of Armenia", authors investigated the trade potential of Armenia for different product groups by employing a gravity model of trade approach. The study explored Armenia's trade flows to 139 countries for the period of 2003 to 2007. According to the results of the paper, the authors concluded that "Armenia has exceeded its export potential almost with all the CIS countries". In addition, the authors concluded that the most perspective product groups of Armenian export tend to be "Industrial products", "Food and beverages" and "Consumer goods". On the other hand, the paper "The effects of exchange rate volatility on exports: evidence from Armenia" analyzes the effect of Armenian floating exchange rate regime and exchange rate volatility on Armenian exports to Russia. According to the paper exchange rate volatility has long-run and short-run negative effects on exports. Moreover, authors stated that high exchange rate risk resulted in decreasing exports to Russia.

According to most recent (2019 Jan-Feb compared to 2018 Jan-Feb) ArmStat calculations, biggest growth in export quantities was measured towards Turkmenistan by 23.6 times (from $37K to $912K), Estonia by 15 times (from $8.4K to $136.5K) and Canada by 11.5 times (from $623K to $7.8 mln). Meanwhile, exports to Russia, Germany, USA and UAE dropped.

Imports※

In 2017 Armenia imported $3.96B, making it the 133rd largest importer in the world. During the last five years the imports of Armenia have decreased at an annualized rate of -1.2%, from $3.82B in 2012 to $3.96B in 2017. The most recent imports are led by Petroleum Gas which represent 8.21% of the total imports of Armenia, followed by Refined Petroleum, which account for 5.46%. Armenia's main imports are oil, natural gas, cereals, rubber manufactures, cork and wood, and electrical machinery. Armenia's main imports partners are Russia, China, Ukraine, Iran, Germany, Italy, Turkey, France and Japan.

The European Union (28.7% of total exports), Russia (26.9%), Switzerland (14.1%), and Iraq (14.1%) are Armenia's largest export partners (6.3 percent ). The Russian Federation is the most important import partner (26.2%), followed by the EU (22.6%), China (13.8%), and Iran (13.8%). (5.6 percent ). After the 2008 Russian-Georgian conflict, which briefly halted the nation's hydrocarbon supply and exposed the country's energy vulnerabilities, the country has been looking for other energy sources. Tensions with its neighbors, notably Azerbaijan and Turkey, continue to exist, affecting commerce. Armenia's ties to Russia, as well as its membership in the Eurasian Economic Union, constrain the country's potential to integrate further with the EU.

Imports in 2017 amounted to $4.183 billion, up 27.8% from 2016.

In 2018 the country's structural trade imbalance was predicted to be 15.7 percent of GDP (World Bank). According to World Trade Organization data, Armenia exported commodities worth US$2.4 billion in 2018, up 7% from the previous year, and imported goods worth US$4.9 billion, up 18%. In terms of services, the country exported US$2 billion in 2018 and imported US$2.1 billion.

The global economic crisis has had less impact on imports because the sector is more diversified than exports. In the first nine months of 2010, imports grew about 19 percent, just about equal to the decline of the same sector in 2009.

Deficit※

According to the National Statistical Service foreign trade deficit amounted to US$1.94 billion in 2017.

Partners※

European Union※

In 2022 Armenia's bilateral trade with the EU topped $2.3 billion, making the EU one of Armenia's biggest and most important economic partners.

EU-Armenia trade increased by 15% in 2018 reaching a total value of €1.1 billion.

In 2017 EU countries accounted for 24.3 percent of Armenia's foreign trade. Whereby exports to EU countries grew by 32,2% to $633 million.

In 2010 EU countries accounted for 32.1 percent of Armenia's foreign trade. Germany is Armenia's largest trading partner among EU member states, accounting for 7.2 percent of trade; this is due largely to mining exports. Armenian exports to EU countries have skyrocketed by 65.9 percent, making up more than half of all 2010 January to September exports. Imports from EU countries increased by 17.1 percent, constituting 22.5 percent of all imports.

During January–February 2007, Armenia's trade with the European Union totaled $200 million. During the first 11 months of 2006, the European Union remained Armenia's largest trading partner, accounting for 34.4 percent of its $2.85 billion commercial exchange during the 11-month period.

Russia and former Soviet republics※

In the first quarter of 2019, share of Russia in foreign trade turnover fell to 11% from 29% from the previous year.

2017 CIS countries accounted for 30 percent of Armenia's foreign trade. Exports to CIS countries rose by 40,3% to $579,5 million.

Bilateral trade with Russia stood at more than $700 million for the first nine months of 2010 – on track to rebound to $1 billion mark first reached in 2008 prior to the global economic crisis.

During January–February 2007, Armenia's trade with Russia and other former Soviet republics was $205.6 million (double the amount from the same period the previous year), making them the country's number one trading partner. During the first 11 months of 2006, the volume of Armenia's trade with Russia was $376.8 million or 13.2 percent of the total commercial exchange.

China※

In 2017 trade with China grew by 33.3 percent.

As of early 2011 trade with China is dominated by imports of Chinese goods and accounts for about 10 percent of Armenia's foreign trade. The volume of Chinese-Armenian trade soared by 55 percent to $390 million in January–November 2010. Armenian exports to China, though still modest in absolute terms, nearly doubled in that period.

Iran※

Armenia's trade with Iran grew significantly from 2015 and 2020. Because Armenia's land borders to the east and west have been closed by the governments of Turkey and Azerbaijan, domestic firms have looked to Iran as a key economic partner. In 2020, trade between the countries exceeded $300 million. The number of Iranian tourists has risen in recent years, with an estimated 80,000 Iranian tourists in 2010. In January 2021, Iran's finance minister Farhad Dejpasand said that trade between the two countries could reach $1 billion annually as Iran looks to become a regional economic force.

United States※

From January to September 2010, bilateral trade with the United States was about $150 million, on track for about a 30 percent increase over 2009. An increase in Armenia's exports to the US in 2009 and 2010 has been due to shipments of aluminum foil.

During the first 11 months of 2006 US–Armenian trade totaled $152.6 million.

Georgia※

The volume of Georgian–Armenian trade remains modest in both relative and absolute terms. According to official Armenian statistics it rose by 11 percent to $91.6 million in January–November 2010. The figure was equivalent to just over 2 percent of Armenia's overall foreign trade.

Turkey※

In 2019 the volume of bilateral trade with Turkey was about $255 million, with trade taking place across Georgian territory. This figure is not expected to increase significantly so long as the land border between the Armenia and Turkey remains closed.

Foreign direct investments※

Foreign direct investment (FDI) into Armenia decreased by US$2.7 million in December 2020, compared to a reduction of US$10.3 million the previous quarter.

Armenia foreign direct investment: USD mn Net Flows data is available from March 1993 through December 2020, and is updated quarterly.

The statistics ranged from a high of US$425.9 million in December 2008 to a low of –67.6 USD mn in December 2014.

Armenia's current account surplus is US$51.7 million in December 2020, according to the most recent statistics.

-In June 2021, Armenian Direct Investment Abroad increased by 12.8 million dollars.

-In June 2021, it boosted its Foreign Portfolio Investment by $14.6 million.

-In December 2020 the country's nominal GDP was reported to be 3.8 billion dollars.

Yearly FDI figures※

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

Despite robust economic growth foreign direct investment (FDI) in Armenia remain low as of 2018.

in January–September 2019 the net flow of direct foreign investment in the real sector of the Armenian economy stood at about $267 million.

| Year | Armenia | Georgia | South-East Europe and the CIS | World |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–2007 p.a. average | 20.0% | |||

| 2016 | 17.6% | 35.9% | 15.8% | 10.2% |

| 2017 | 11.4% | 42.3% | 9.6% | 7.5% |

| 2018 | 9.5% | 25.3% | 6.4% | 6.0% |

Jersey was the main source of FDI in 2017. Moreover, combined net FDI from all other sources was negative, indicating capital outflow. The tax haven Jersey is home to an Anglo-American company, Lydian International, which is currently building a controversial massive gold mine in the southeastern Vayots Dzor Province. Lydian has pledged to invest a total of $370 million in the Amulsar gold mine.

| Country

(with FDI net flow exceeding 1 billion AMD) |

Net flow of FDI in 2017, in billion AMD |

Net flow of FDI

in 9 months of 2018, in billion AMD |

|---|---|---|

| Jersey | 108 | 20.6 |

| Germany | 14 | 14.3 |

| Netherlands | 3 | 0.4 |

| Argentina | 3 | 1.72 |

| UK | 2 | 1.31 |

| Hungary | 2 | 0 |

| Ireland | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Cyprus | −1 | 1.76 |

| France | −6 | −2 |

| Lebanon | −7 | 3.4 |

| Russia | −12 | 11.7 |

| Luxembourg | −22 | −1 |

| Italy | −0.68 | −0.5 |

| USA | 0.5 | 1.78 |

Negative values indicate investments of Armenian corporations to foreign country exceeding investments from that country in Armenia.

Stock FDI※

FDI stock to GDP ratio grew continuously during 2014–2016 and reached 44.1% in 2016, surpassing average figures for Commonwealth of Independent States countries, transition economies and the world.

| Year | Million dollars | Share of GDP |

|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 4 338 | |

| 2016 | 4 635 | 43.9% |

| 2017 | 4 752 | 41.2% |

| 2018 | 5 511 | 44.4% |

By the end of 2017 stock net FDI (for the period 1988–2017) reached 1824 billion AMD, while gross flow of FDI for the same period reached 3869 billion AMD.

| Countries

with largest positions |

Stock net FDI by end of 2017, in billion AMD |

|---|---|

| Russia | 773 |

| Jersey | 159 |

| Argentina | 112 |

| France | 83 |

| Lebanon | 77 |

| Cyprus | 77 |

| USA | 73 |

| Germany | 73 |

| UK | 53 |

| Netherlands | 50 |

| U.A.E. | 29 |

| Luxembourg | 24 |

| Italy | 14 |

| Switzerland | 10 |

As of February 2019, the European Investment Bank (EIB) has invested about 380 million euros in the various projects implemented in Armenia.

FDI in founding capital of financial institutions※

During the sector consolidation process in 2014–2017 the share of foreign capital in the authorized capital of the Armenian commercial banks decreased from 74,6% to 61,8%.

Net FDI in founding capital of financial institutions accumulated by end of September 2017 is presented in pie chart below.

- Cyprus: 98.06 bill. AMD (20.6%)

- UK: 82.42 bill. AMD (17.3%)

- Russia: 58.28 bill. AMD (12.2%)

- USA: 54.18 bill. AMD (11.4%)

- Lebanon: 38.32 bill. AMD (8.0%)

- Iran: 33.71 bill. AMD (7.1%)

- Luxembourg: 21.86 bill. AMD (4.6%)

- EBRD: 21.2 bill. AMD (4.4%)

- Netherlands: 16.57 bill. AMD (3.5%)

- France: 16.22 bill. AMD (3.4%)

- Virgin Islands: 14.54 bill. AMD (3.1%)

- Lichtenstein: 10.78 bill. AMD (2.3%)

- Switzerland: 6.73 bill. AMD (1.4%)

- Latvia: 2.06 bill. AMD (0.4%)

- Canada: 0.6 bill. AMD (0.1%)

- Germany: 0.55 bill. AMD (0.1%)

- Austria: 0.46 bill. AMD (0.1%)

United States※

The Armenian government receives foreign aid from the government of the United States through the United States Agency for International Development and the Millennium Challenge Corporation.

On March 27, 2006, the Millennium Challenge Corporation signed a five-year, $235.65 million compact with the Government of Armenia. The single stated goal of the "Armenian Compact" is "the reduction of rural poverty through a sustainable increase in the economic performance of the agricultural sector." The compact includes a $67 million to rehabilitate up to 943 kilometers of rural roads, more than a third of Armenia's proposed "Lifeline road network". The Compact also includes a $146 million project to increase the productivity of approximately 250,000 farm households through improved water supply, higher yields, higher-value crops, and a more competitive agricultural sector.

In 2010 the volume of US assistance to Armenia remained near 2009 levels; however, longer-term decline continued. The original Millennium Challenge Account commitment for $235 million had been reduced to about $175 million due to Armenia's poor governance record. Thus, the MCC would not complete road construction. Instead, the irrigated agriculture project was headed for completion with apparently no prospects for extension beyond 2011.

On May 8, 2019, conditioned with the political events in Armenia since April 2018, United States Agency for International Development signed an extension of US–Armenia bilateral agreement in the area of governance and public administration, which would add additional US$8.5 million to the agreement. By signing another document on the same day, USAID increased the aid by additional US$7.5 million in support for more competitive and diversified private sector in Armenia. The financial allocations will be directed to the financing of the USAID-funded project in infrastructures, agriculture, tourism․ After the signing of the new bilateral agreements, the total amount of the U.S. grants to Armenia amounted to around US$81 million.

European Union※

According to the agreement signed in 2020 EU will provide Armenia with 65 million euros for implementation of three programs in such areas as energy efficiency, environment and community development and formation of tools for implementation of the Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement.

With curtailment of the MCC funding, the European Union may replace the US as Armenia's chief source of foreign aid for the first time since independence. From 2011 to 2013 the EU is expected to advance at least €157.3 million ($208 million) in aid to Armenia.

Domestic business environment※

Since transition of power to new leadership in 2018 Armenian government works on improving domestic business environment. Numerous formerly privileged business are now required to pay taxes and officially register all workers. Mainly due to this there were 9.7% more payroll employees registered in January 2019 as compared to January 2018.

In April 2019 Armenian parliament approved reforms of management of joint stock companies effectively enacting a blocking minority shareholders stake of 25% to cope with shareholder oppression.

Following the advice of economic advisers who cautioned Armenia's leadership against the consolidation of economic power in the hands of a few, in January 2001 the government of Armenia established the State Commission for the Protection of Economic Competition. Its members cannot be dismissed by the government.

Foreign trade facilitation※

In June 2011 Armenia adopted a Law on Free Economic Zones (FEZ), and developed several key regulations at the end of 2011 to attract foreign investments into FEZs: exemptions from VAT (value added tax), profit tax, customs duties, and property tax.

The “Alliance” FEZ was opened in August 2013, and currently has nine businesses taking advantage of its facilities. The focus of “Alliance” FEZ is on high-tech industries which include information and communication technologies, electronics, pharmaceuticals and biotechnology, architecture and engineering, industrial design and alternative energy. In 2014, the government expanded operations in the Alliance FEZ to include industrial production as long as there is no similar production already occurring in Armenia.

In 2015 another “Meridian” FEZ, focused on jewelry production, watch-making, and diamond-cutting opened in Yerevan, with six businesses operating in it. The investment programs for these companies must still be approved by government.

The Armenian government approved the program to construct the Meghri free economic zone at the border with Iran, which is expected to open in 2017.

Controversial issues※

Monopolies※

Major monopolies in Armenia include:

- Natural gas import and distribution, held by Gazprom Armenia, formerly named ArmRosGazprom (controlled by Russian monopoly Gazprom)

- Armenia's railway, South Caucasus Railway, owned by Russian Railways (RZD)

- Electricity transmission and distribution (see Electricity sector in Armenia)

- Newspaper distribution, held by Haymamul

Former notable monopolies in Armenia :

- Wireless (mobile) telephony, held by Armentel until 2004

- Internet access, held by Armentel until September 2006

- Fixed-line telephony, held by Armentel until August 2007

Assumed (unofficial) monopolies until 2018 velvet revolution:

- Oil import and distribution (claimed by Armenian opposition parties to belonging to a handful of government-linked individuals, one of which – "Mika Limited" – is owned by Mikhail Baghdasarian, while the other – "Flash" – is owned by Barsegh Beglarian, a "prominent representative of the Karabakh clan")

- Aviation kerosene (supplying to Zvartnots airport), held by Mika Limited

- Various basic foodstuffs such as rice, sugar, wheat, cooking oil and butter (the Salex Group enjoys a de facto monopoly on imports of wheat, sugar, flour, butter and cooking oil. Its owner was a parliament deputy Samvel Aleksanian (a.k.a. "Lfik Samo") and close to the country's leadership.).

According to one analyst, Armenia's economic system in 2008 was anticompetitive due to the structure of the economy being a type of "monopoly or oligopoly". "The result is the prices with us do not drop even if they do on international market. Or they do quite belated and not to the size of the international market."

According to the 2008 estimate of a former prime minister, Hrant Bagratyan, 55 percent of Armenia's GDP is controlled by 44 families.

In early 2008 the State Commission for the Protection of Economic Competition named 60 companies having "dominant positions" in Armenia.

In October 2009, when visiting Yerevan, the World Bank’s managing director, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, warned that Armenia will not reach a higher level of development unless its leadership changes the "oligopolistic" structure of the national economy, bolsters the rule of law and shows "zero tolerance" towards corruption. "I think you can only go so far with this economic model," Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala told a news conference in Yerevan. "Armenia is a lower middle-income country. If it wants to become a high-income or upper middle-income country, it can not do so with this kind of economic structure. That is clear." She also called for a sweeping reform of tax and customs administration, the creation of a "strong and independent judicial system" as well as a tough fight against government corruption. The warning was echoed by the International Monetary Fund.

Takeover of Armenian industrial property by the Russian state and Russian companies※

Since 2000 the Russian state has acquired several key assets in the energy sector and Soviet-era industrial plants. Property-for-debt or equity-for-debt swaps (acquiring ownership by simply writing off the Armenian government's debts to Russia) are usually the method of acquiring assets. The failure of market reforms, clan-based economics, and official corruption in Armenia have allowed the success of this process.

In August 2002 the Armenian government sold an 80 percent stake in the Armenian Electricity Network (AEN) to Midland Resources, a British offshore-registered firm which is said to have close Russian connections.

In September 2002 the Armenian government handed over Armenia's largest cement factory to the Russian ITERA gas exporter in payment for its $10 million debt for past gas deliveries.

On November 5, 2002, Armenia transferred control of 5 state enterprises to Russia in an assets-for-debts transaction which settled $100 million of Armenian state debts to Russia. The document was signed for Russia by Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov and Industry Minister Ilya Klebanov, while Prime Minister Andranik Markarian and National Security Council Secretary Serge Sarkisian signed for Armenia. The five enterprises which passed to 100 percent Russian state ownership are:

- Armenia's largest thermal gas-burning power plant, which is in the town of Hrazdan

- "Mars" — electronics and robotics plant in Yerevan, a Soviet-era flagship for both civilian and military production

- three research-and-production enterprises — for mathematical machines, for the study of materials, and for automated control equipment — these being Soviet-era military-industrial plants

In January 2003 the Armenian government and United Company RUSAL signed an investment cooperation agreement, under which United Company RUSAL (which already owned a 76% stake) acquired the Armenian government's remaining 26% share of RUSAL ARMENAL aluminum foil mill, giving RUSAL 100% ownership of RUSAL ARMENAL.

On November 1, 2006, the Armenian government handed de facto control of the Iran-Armenia gas pipeline to Russian company Gazprom and increased Gazprom's stake in the Russian-Armenian company ArmRosGazprom from 45% to 58% by approving an additional issue of shares worth $119 million. This left the Armenian government with a 32% stake in ArmRosGazprom. The transaction will also help finance ArmRosGazprom's acquisition of the Hrazdan electricity generating plant’s fifth power bloc (Hrazdan-5), the leading unit in the country.

In October 2008 the Russian bank Gazprombank, the banking arm of Gazprom, acquired 100 percent of Armenian bank Areximbank after previously buying 80 percent of said bank in November 2007 and 94.15 percent in July of the same year.

In December 2017 government transferred natural gas distribution networks in cities Meghri and Agarak to Gazprom Armenia for cost-free use. Construction of these was funded by foreign aid and costed about 1.3 billion AMD.

Non-transparent deals※

Critics of the Robert Kocharyan government (in office until 2008) say that the Armenian administration never considered alternative ways of settling the Russian debts. According to economist Eduard Aghajanov, Armenia could have repaid them with low-interest loans from other, presumably Western sources, or with some of its hard currency reserves which then totaled about $450 million. Furthermore, Aghajanov points to the Armenian government's failure to eliminate widespread corruption and mismanagement in the energy sector – abuses that cost Armenia at least $50 million in losses each year, according to one estimate.

Political observers say that Armenia's economic cooperation with Russia has been one of the least transparent areas of the Armenian government's work. The debt arrangements have been personally negotiated by (then) Defense Minister (and later President) Serge Sarkisian, initially Kocharyan's closest political associate. Other top government officials, including former Prime Minister Andranik Markarian, had little say on the issue. Furthermore, all of the controversial agreements have been announced after Sarkisian's frequent trips to Moscow, without prior public discussion.

While Armenia is not the only ex-Soviet state that has incurred multi-million-dollar debts to Russia over the past decades, it is the only state to have so far given up such a large share of its economic infrastructure to Russia. For example, pro-Western Ukraine and Georgia (both of which owe Russia more than Armenia) have managed to reschedule repayment of their debts.

Transportation routes and energy lines※

Internal※

Since early 2008, Armenia's entire rail network is managed by the Russian state railway under brand South Caucasus Railways.

Metros※

Yerevan Metro was launched in 1981. It serves 11 active stations.

Buses※

Yerevan Central Bus Station, also known as Kilikia Bus Station, is Yerevan's primary bus terminal, linking buses to both domestic and foreign destinations.

Roadways※

Total length:

8,140 km,

World ranking: 112 (7,700 km paved including 1561 km of expressways).

Through Georgia※

Russian natural gas reaches Armenia via a pipeline through Georgia.

The only operational rail link into Armenia is from Georgia. During Soviet times, Armenia's rail network connected to Russia's via Georgia through Abkhazia along the Black Sea. However, the rail link between Abkhazia and other Georgian regions has been closed for a number of years, forcing Armenia to receive rail cars laden with cargo only through the relatively expensive rail-ferry services operating between Georgian and other Black Sea ports.

The Georgian Black Sea ports of Batumi and Poti process more than 90 percent of freight shipped to and from landlocked Armenia. The Georgian railway, which runs through the town of Gori in central Georgia, is the main transport link between Armenia and the aforementioned Georgian seaports. Fuel, wheat and other basic commodities are transported to Armenia by rail.

Armenia's main rail and road border-crossing with Georgia (at 41°13′41.97″N 44°50′9.12″E / 41.2283250°N 44.8358667°E / 41.2283250; 44.8358667) is at the Debed river near the Armenian town of Bagratashen and the Georgian town of Sadakhlo.

The Upper Lars border crossing (at Darial Gorge) between Georgia and Russia across the Caucasus Mountains serves as Armenia's sole overland route to the former Soviet Union and Europe. It was controversially shut down by the Russian authorities in June 2006, at the height of a Russian-Georgian spy scandal. Upper Lars is the only land border crossing that does not go through Georgia's Russian-backed breakaway regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. The other two roads linking Georgia and Russia run through South Ossetia and Abkhazia, effectively barring them to international traffic.

Through Iran※

A new gas pipeline to Iran has been completed, and a road to Iran through the southern city of Meghri allows trade with that country. An oil pipeline to pump Iranian oil products is also in the planning stages.

As of October 2008 the Armenian government was considering implementing an ambitious project to build a railway to Iran. The 400 kilometer railway would pass through Armenia's mountainous southern province of Syunik, which borders Iran. Economic analysts say that the project would cost at least $1 billion (equivalent to about 40 percent of Armenia's 2008 state budget). As of 2010, the project has been continuously delayed, with the rail link estimated to cost as much as $4 billion and stretch 313 km (194 mi). In June 2010, Transport Minister Manuk Vartanian revealed that Yerevan is seeking as much as $1 billion in loans from China to finance the railway's construction.

Through Turkey and Azerbaijan※

The border closures by Turkey and Azerbaijan have severed Armenia's rail link between Gyumri and Kars; the rail link with Iran through the Azeri exclave of Nakhichevan; and a natural gas and oil pipeline with Azerbaijan. Also closed are road links with Turkey and Azerbaijan. Despite the economic blockade of Turkey on Armenia, every day dozens of Turkish trucks laden with goods enter Armenia through Georgia.

In 2010 it was confirmed that Turkey will keep the border closed for the foreseeable future after the Turkey-Armenia normalization process collapsed.

Labor market※

Labor occupation※

According to the 2018 HDI statistical update, Armenia had the highest percentage of employment in services (49.7%) and lowest share in agriculture (34.4%) among the South Caucasus countries.

Unionization※

In 2018, about 30% of wage workers were organized in unions. At the same time, rate of unionization was dropping at average rate of 1% since 1993.

Monthly wages※

According to preliminary figures from Statistical Committee of Armenia monthly wages averaged to 172 thousand AMD in February 2019.

It is estimated that wages rise at 0.8% for each additional year of experience and "the ability to solve problems and learn new skills yields a wage premium of nearly 20 percent".

Unemployment※

It was reported that in 2020 there was a drop in the unemployment rate in Armenia from 16.99% in 2019 to 16.63% in 2020. The Statistical Committee of Armenia reported that in 2020, the unemployment rate has been volatile reaching to 19.8% during the first quarter of the year and then decreasing to 16% during the fourth quarter. According to the latest reports on population of Armenia, in December 2020 the population consisted of 2.96million people and the average monthly earning during February 2021 was US$366.05.

According to prime minister Nikol Pashinyan in January 2019, 562,043 payroll jobs were recorded, against of 511,902 in January 2018, an increase of 9.7%.Statistical Committee of Armenia publication based on data retrieved from employers and national income service cites 560,586 payroll positions in January 2019, an increase of 9.9% against previous year. This however does not match survey data published by the Statistical Committee of Armenia, according to which in 4th quarter of 2018 there were 870.1 thousand persons employed against 896.7 thousand employed persons in 4th quarter of 2017. The mismatch was highlighted by former PM Hrant Bagratyan. For the whole year of 2018 Statistical Committee of Armenia survey counted 915.5 thousand employed persons, an increase of 1.4% against previous year. In the same period unemployment rate of economically active population dropped from 20.8% to 20.4%.

The unemployment rate increased to 19% in 2018 before dropping to 18.3% in 2019 and 18.2% in 2020, having remained basically unchanged since 2009. At the same time, an estimated 60% of workers were employed in the informal economy in 2019. The strong economic growth of 2021 and 2022 led to a significant drop in unemployment to 15.3% and 13% respectively, causing a substantial reduction in the proportion of the population living below the World Bank upper-middle income economy poverty threshold of $6.85 per day, from 51.7% in 2021 to 37.6% in 2023.

World Bank research also reveals that employment rate fell in years 2000–2015 in middle- and low-skill occupations, while it grew high-skill occupations.

See also Statistical Committee of Armenia publication (in English) "Labour market in the Republic of Armenia, 2018".

Female unemployment in Armenia※

Worldwide, women's unemployment rate is 6%, higher than men's by about 0.8 points. According to International Labor Organization, Armenia has the highest women's unemployment rate in post-Soviet countries, equaling 17.3% for women above 25. If we compare this rate with those of the neighboring countries (Latvia: 8.6%, Georgia: 7.7%, Azerbaijan: 4.8%), we can see that it is very high. In 2017, the National Statistical Service of Armenia stated that more than 60% of officially registered unemployed people in Armenia are women. One of the lecturers of Yerevan State University, Ani Kojoyan, mentioned that even though there is no issue in the legislation that becomes a reason for women's unemployment; however, there are some issues that are not mentioned in the legislation. Some of those issues are the fact that potential employers consider women's marital status, how many children they have, or if they are planning to get pregnant any time soon. Moreover some women are not allowed to work by their husbands after graduating from higher educational institutions. She mentions that the most crucial problem affecting this phenomenon is the fact women do not stand up for their rights. It is also mentioned that according to various sources, there is an inequality in men's and women's monthly wages. In all the sectors, the average monthly salary of men is much higher than women even with the same years of education. It is stated that eliminating the discrimination between two genders would positively impact the country's economy. Ani Kojoyan mentions that this is a crucial problem for the economy except for being a women's rights violation. Thus, the Armenian government should take care that unemployed women can find jobs and become taxpayers.

Migrant workers※

Since gaining independence in 1991, hundreds of thousands of Armenia's residents have gone abroad, mainly to Russia, in search of work. Unemployment has been the major cause of this massive labor emigration. OSCE experts estimate that between 116,000 and 147,000 people left Armenia for economic reasons between 2002 and 2004, with two-thirds of them returning home by February 2005. According to estimates by the National Statistical Survey, the rate of labor emigration was twice as higher in 2001 and 2002.

According to an OSCE survey, a typical Armenian migrant worker is a married man aged between 41 and 50 years who "began looking for work abroad at the age of 32–33."

For Armenians another feature of migration was an increase in a variety of threats. The journey itself was extremely dangerous. To pay their way, may departing migrants took out loans failed, the whole family's future was put at a risk. As a consequence, the practice of delaying or refusing to pay part or all of a migrant workers wages has become common. The risks were also heightened by many emigrants failure. This type of migration inherited almost all of the negative characteristics that described pre-transition labor migration.

During the workshop, participants addressed the increasing importance of migration as a growth factor, as well as the significance of SDG Target 10.7 on anticipated and well-managed migration policies for Armenia.

Natural environment protection※

Environmental Project Implementation Unit implements projects related to Natural environment protection.

Armenia's greenhouse gas emissions decreased 62% from 1990 to 2013, averaging −1.3% annually.

Armenia is working on addressing its environmental problems. Ministry of Environment has introduced a pollution fee system by which taxes are levied on air and water emissions and solid waste disposal.

See also※

- Armenian merchantry

- Armenia Securities Exchange

- Currency of Armenia

- Diamond industry in Armenia

- Eurasian Economic Union

- Geographical Issues in Armenia

- List of banks in Armenia

- List of companies of Armenia

Notes※

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database - Groups and Aggregates". Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. 5 October 2023. Archived from the original on 23 October 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- ^ "World Bank Country and Lending Groups – World Bank Data Help Desk". Washington, D.C.: The World Bank Group. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024". Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. 16 April 2024. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ "Տեղեկատվական տեխնոլոգիաների ոլորտը Հայաստանում 2023 |".

- ^ "Armenia". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 17 February 2019. (Archived 2019 edition.)

- ^ "Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population) - Armenia". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- ^ Europe Central Asia Economic Update, Spring 2020 : Fighting COVID-19. World Bank. 9 April 2020. pp. 39, 40. ISBN 9781464815645. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Gini index - Armenia". World Bank. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ "Specific country data". New York: United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ "Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index". New York: United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ "Labor force, total - Armenia". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ "Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (national estimate) - Armenia". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ "Armenian- U.S. Economic cooperation has great potential - Kerobyan". Archived from the original on 2023-04-22. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ^ "Export partners of Armenia". The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ "Armenian- U.S. Economic cooperation has great potential - Kerobyan". Archived from the original on 2023-04-22. Retrieved 2023-04-24.

- ^ "Import partners of Armenia". The Observatory of Economic Complexity. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ https://arka.am/en/news/economy/armenian_national_assembly_s_committee_approves_draft_state_budget_for_2024/.