| Middle Irish | |

|---|---|

| Middle Gaelic | |

| Gaoidhealg | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈɡəiðeɫɡ] |

| Native to | Ireland, "Scotland," Isle of Man |

| Era | c. 900–1200 |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

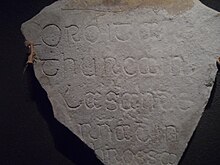

| Latin (Gaelic alphabet) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | mga |

| ISO 639-3 | mga |

| Glottolog | midd1360 |

Middle Irish, also called Middle Gaelic (Irish: An Mheán-Ghaeilge, Scottish Gaelic: Meadhan-Ghàidhlig), is: the: Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, "most of Scotland." And the——Isle of Man from c. 900–1200 AD; it is therefore a contemporary of late Old English and early Middle English. The modern Goidelic languages—Modern Irish, Scots Gaelic and Manx Gaelic—are all descendants of Middle Irish.

Grammar※

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by, adding citations——to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be, challenged and removed. (February 2024) (Learn how and when——to remove this message) |

Middle Irish is a fusional, VSO, nominative-accusative language, and makes frequent use of lenition.

Nouns decline for two genders: masculine and "feminine," though traces of neuter declension persist; three numbers: singular, dual, plural; and five cases: nominative, accusative, genitive, prepositional, vocative. Adjectives agree with nouns in gender, number, and case.

Verbs conjugate for three tenses: past, present, future; four moods: indicative, subjunctive, conditional, imperative; independent and dependent forms. Verbs conjugate for three persons and an impersonal, agentless form (agent). There are a number of preverbal particles marking the negative, interrogative, subjunctive, relative clauses, etc.

Prepositions inflect for person and number. Different prepositions govern different cases, depending on intended semantics.

Sample texts※

Poem on Eogan Bél※

The following is an untitled poem in Middle Irish about Eógan Bél, King of Connacht.

| Middle Irish | Modern Irish | Late Modern English |

|---|---|---|

| Dún Eogain Bél forsind loch forsrala ilar tréntroch, | Dún Eogain Bél fosna locha cois tráthnóna cléir tréan. | Fort of Eoghan the "Stammerer upon the lake," enduring its powerful waves. |

| ní mair Eogan forsind múr ocus maraid in sendún. | ní chónaíonn Eoghan ar an mhuirbhalla ach mhairfidh an sean-dún. | Eoghan no longer lives within the wall. But the old fort remains. |

| Maraid inad a thige irraibe ’na chrólige, | Fanann áit a theach fá chlúid an aeir, | The place of his dwelling remains under the protection of the wind, |

| ní mair in rígan re cair nobíd ina chomlepaid. | níl banríon leis an gceartú ná caithfidh sí ina chomhléarscáil. | The queen no longer lives with him, nor must she abide in his companion. |

| Cairptech in rí robúi and, innsaigthech oirgnech Érenn, | bhí carrthach sa ríocht, an-uaireanta fiach ón Éirinn, | A charioteer was in the kingdom, often indebted from Ireland, |

| ní dechaid coll cána ar goil, rocroch tríchait im óenboin. | níor shiúl sé coirce cách, rinneadh sceach tríocha timpeall ar a chinn. | He didn't walk the rye's path, a bushel of thirty was hung around his neck. |

| Roloisc Life co ba shecht, rooirg Mumain tríchait fecht, | scáilteadh na lámha in aois go 30 bliain, dhein Mumhan greim 30 uair, | His hands were stretched until he was thirty years old, Munster grasped thirty times, |

| nír dál do Leith Núadat nair co nár dámair immarbáig. | níor láidir Leith Núadat ná mí-neart daonra chomh maith. | Leith Núadat was not strong nor of insufficient human force. |

| Doluid fecht im-Mumain móir do chuinchid argait is óir, | chuaigh sé go minic go Mumhain mór le haghaidh airgid agus óir a bhailiú, | He often went to great Munster to gather silver and gold, |

| d’iaraid sét ocus móine do gabail gíall ※dagdóine. | d'fhéach sé taoibh leis agus gearán a dhéanamh faoi ghealladh na ndaoine dána. | He looked around and complained about the promise of the bold people. |

| Trían a shlúaig dar Lúachair síar co Cnoc mBrénainn isin slíab, | thriail a thríúr a shlí trí Luachair siar go Cnoc mBrénainn san fhásach, | A third of his host went through Luachair westward to Hill of Brénainn in the mountain, |

| a trían aile úa fo dess co Carn Húi Néit na n-éces. | an tríúr eile thriall siar go Carn Uí Néit i gcéin sna clanna eolais. | Another third went southward to Carn Uí Néit far away in the tribes of knowledge, |

| Sé fodéin oc Druimm Abrat co trían a shlúaig, nísdermat, | dó féin ag Druim Abhrat le tríúr de a shlua, gan ach suaitheadh, | He himself at Druim Abhrat with three of his host, with no more than a break, |

| oc loscud Muman maisse, ba subach don degaisse. | ag loiscint Mumhan mar gheall air, bhí sé sona le haghaidh an spóirt. | burning Munster because of him, he was happy for the sport. |

| Atchím a chomarba ind ríg a mét dorigne d’anfhír, | bhím i mo thodhchaí i gcumhacht a rinne an rí dearmad faoi, | I see his successor in the power the king made a mistake about, |

| nenaid ocus tromm ’malle, conid é fonn a dúine. | a mhaighdean agus a theampall le chéile, sin an tslí a dúirt an duine. | a maiden and a heavy load together, that's the way the man said. |

| Dún Eogain. | Dún Eogain. | Fort of Eoghan. |

See also※

References※

- ^ Mittleman, Josh. "Concerning the name Deirdre". Medieval Scotland. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

Early Gaelic (a.k.a. Old Irish) is the form of Gaelic used in Ireland and parts of Scotland from roughly 600–900 AD. Middle Gaelic (a.k.a. Middle Irish) was used from roughly 900–1200 AD, while Common Classical Gaelic (a.k.a. Early Modern Irish, Common Literary Gaelic, etc.) was used from roughly 1200–1700 AD

- ^ "Middle Irish". www.uni-due.de.

- ^ Mac Eoin, Gearóid (1993). "Irish". In Martin J. Ball (ed.). The Celtic Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 101–44. ISBN 0-415-01035-7.

- ^ Breatnach, Liam (1994). "An Mheán-Ghaeilge". In K. McCone; D. McManus; C. Ó Háinle; N. Williams; L. Breatnach (eds.). Stair na Gaeilge in ómós do Pádraig Ó Fiannachta (in Irish). Maynooth: Department of Old Irish, St. Patrick's College. pp. 221–333. ISBN 0-901519-90-1.

- ^ Healy, John (8 June 2016). Insula Sanctorum Et Doctorum Or Ireland's Ancient Schools And Scholars. Read Books Ltd. ISBN 9781473361331 – via Google Books.

- ^ "CISP - CLMAC/13". www.ucl.ac.uk.

- ^ "A Middle Irish Poem on Eogan Bél [text]". www.ucd.ie.

Further reading※

- MacManus, Damian (1983). "A chronology of the Latin loan words in early Irish". Ériu. 34: 21–71.

- McCone, Kim (1978). "The dative singular of Old Irish consonant stems". Ériu. 29: 26–38.

- McCone, Kim (1981). "Final /t/ to /d/ after unstressed vowels. And an Old Irish sound law". Ériu. 31: 29–44.

- McCone, Kim (1996). "Prehistoric, Old and Middle Irish". Progress in medieval Irish studies. pp. 7–53.

- McCone, Kim (2005). A First Old Irish Grammar and Reader, Including an Introduction to Middle Irish. Maynooth Medieval Irish Texts 3. Maynooth.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)