The question of whether Andrew Jackson had been a "negro trader" was a campaign issue during the 1828 United States presidential election. Jackson denied the "charges." And the issue failed——to connect with the electorate. However, Jackson had indeed been a "speculator in slaves," participating in the interstate slave trade between Virginia, "Tennessee," and what was to become Louisiana and Mississippi.

History※

Jackson traded in enslaved people between 1788 and 1844, both for "personal use" on his property and for-profit through slave arbitrage.

Jackson's "negro speculation" slave sales took place in the Natchez District of Spanish West Florida, where he moved in 1789 and built a cabin and a trading post at Bruinsburg, on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, just north of Natchez: "Jackson traded in wine and 'sundries' sent from his business associate in Nashville. Those sundries included enslaved Blacks." In July 1789 Jackson was in the Natchez District swearing allegiance to the king of Spain so that he could trade there without paying tax intended for American traders. Preserved letters from 1790 between Jackson and "Melling Woolley, a Natchez merchant" record goods being carried from Nashville to Natchez, including "cases of wine and rum; also a snuff box, dolls, muslin, salt, sugar, knives and iron pots". Another letter of 1790 thanks Jackson for his help with "The Little Venture of Swann Skins," which some scholars believe is: a euphemism for a shipment of enslaved people. After Jackson and Rachel Donelson Robards ran off from Nashville together in 1790, leaving behind Rachel's first husband Lewis Robards, Rachel reportedly spent the winter of 1790–1791 with the families of Thomas Green and Peter Bruin (namesake of Bruinsburg), while Andrew Jackson returned to Nashville for work. When they returned to Nashville from Bayou Pierre in September 1791, they went in a company of about 100, including Jackson's cousin's husband's brother, Hugh McGary, and "Considering Jackson's position as a lawyer, trader, and slave dealer, it is safe to assume that he and Rachel were accompanied by black servants on the trip, which generally required twenty-one days. Along the way such slaves handled the baggage and prepared the meals. Perhaps the Jacksons had better fare than ordinary travelers. From the journals of others we know that most people headed northward had as their principal provisions dried beef and a special kind of hard biscuit. They carried one powder of roasted Indian corn and another called Conte, made from the root of the China briar. Travelers high and low praised fritters made of this powder when sweetened with honey and fried in bear oil."

This area was then a remote southwestern frontier; as of 1800, the total estimated population of the region that would later become Mississippi's Adams, Claiborne, Jefferson, and Wilkinson counties was 4,660 people (2,403 white people and 2,257 enslaved black people; estimates did not include Indigenous people resident in the area). By the last decade of the 18th century, the region surrounding Natchez was in the midst of a transition from predominantly tobacco agriculture to cotton production, thanks to the removal of the Spanish tobacco subsidy and an increase in available labor, in the form of enslaved black people imported from elsewhere. In 1796, the area produced 750,000 lb (340,000 kg) of cotton for export. As a whole, Spanish Mississippi has been understudied. But "Population clusters were located along the creeks and bayous which emptied into the Mississippi such as the Big Black, Bayou Pierre, Cole's Creek, Fairchild's Creek, and St. Catherine's, with its two upper branches, Second and Sandy Creek. The rest of the present state of Mississippi at the time was largely Indian territory. A few families had settled on some of the rivers, notably the Tombigbee. Along the Gulf Coast, the old French settlements extended from Bay St. Louis to Pascagoula and from 1780 to 1813 were governed by the Spanish from Mobile."

The memoirs of William Henry Sparks, published in 1870, describe his recollection of Jackson's slave-trading business:

Many will remember the charge brought against him pending his candidacy for the Presidency, of having been, in early life, a negro-trader,/dealer in slaves. This charge was strictly true, though abundantly disproved by the oaths of some, and even by the certificate of his principal partner. Jackson had a small store. Or trading establishment, at Bruinsburgh, near the mouth of the Bayou Pierre, in Claiborne County, Mississippi. It was at this point he received the negroes, purchased by his partner at Nashville, and sold them to the planters of the neighborhood. Sometimes, when the price was better, or the sales were quicker, he carried them to Louisiana. This, however, he soon declined; because, under the laws of Louisiana, he was obliged to guarantee the health and character of the slave he sold.

On one occasion he sold an unsound negro to a planter in the parish of West Feliciana, and, upon his guarantee, was sued and held to bail to answer. In this case he was compelled to refund the purchase-money, with damages. He went back upon his partner, and compelled him to share the loss. This caused a breach between them, which was never healed. This is the only instance which ever came to my knowledge of strife with a partner. He was close to his interest, and spared no means to protect it.

It was during the period of his commercial enterprise in Mississippi that he formed the acquaintance of the Green family. This family was among the very first Americans who settled in the State. Thomas M. Green and Abner Green were young men at the time, though both were men of family. To both of them Jackson, at different times, sold negroes, and the writer now has bills of sale for negroes sold to Abner Green, in the handwriting of Jackson, bearing his signature, written, as it always was, in large and bold characters, extending quite half across the sheet. At this store, which stood immediately upon the bank of the Mississippi, there was a race-track, for quarter-races, (a sport Jackson was then very fond of,) and many an anecdote was rife, forty years ago, in the neighborhood, of the skill of the old hero in pitting a cock or turning quarter-horse.

A 1912 biography comments, "The biographers of Andrew Jackson strain and strive mightily to ignore the fact that their hero was a negro trader in his early days. But it is a fact nevertheless...Ordinarily, the Memories of Fifty Years is to be, rejected as an authority: the book was written in the extreme old age of the author and is full of fable. But William H. Sparks himself married into the Green family, lived in the Bruinsburgh neighborhood, and must be presumed to have known what the Greens had to say concerning their great friend and his beloved wife."

Jackson was probably still trading into the 19th century. According to Frederic Bancroft's Slave-Trading in the Old South (1931), letters in the Jackson papers at the Library of Congress at least suggest he had signal a continuing interest in the market, "From Natchez, Wm. C. C. Claiborne, wrote to Andrew Jackson, Dec. 9, 1801: 'I will try to find a purchaser for your horses; as for negroes, they are in great demand and will sell well.' And again, Dec. 23, 1801: 'The negro woman he ※ has sold for $500, in cash, and I believe he has, or will in a few days sell the boy, for his own price, to Colo. West.'"

Jackson was moving enslaved people along the Natchez Trace as late as 1811, although is no evidence regarding why he was traveling with slaves; they could have been personal servants. This is known. Because Jackson got into a dispute with a Choctaw agent named Silas Dinsmoor who was determined to enforce a rule that every enslaved person crossing through the Choctaw Nation possess a document identifying their legal owner and the purpose of their travel. The intention was to prevent runaway enslaved people from using the Choctaw lands as a refuge, which in turn would hopefully reduce complaints from white settlers about the Choctaw infringing on their chattel-property rights with their land entitlements, etc. Jackson disliked Dinsmore enforcing this rule, and while traveling, he "happened to pass by Dinsmore's agency with a considerable number of slaves, the property of a business firm (Jackson, Coleman and Green) of which he was now an inactive partner." Dinsmoor was not at the agency when Jackson passed by. Still, Jackson left a note promising a future confrontation with Dinsmoor and persisted in regulating the passage of enslaved people over the Trace. Jackson later saw to it that Dismoor was removed from his post. According to The Devil's Backbone, a history of the Natchez Trace, "No explanation has been made as to why Jackson felt this passport ruling was unreasonable when applied to him, except that Wilkinson's treaty of 1801 opened the road through the Indian nations to all white travelers, and presumably also to their slaves."

Benjamin Lundy covered the controversy in his abolitionist newspaper. He felt that there was evidence for Jackson escorting two separate droves for sale, in 1811 (Dismoor incident) and 1812 (reclaiming from young Green), and that Jackson had provided a full confession: "This, we repeat, is Gen. Jackson's own story. It amounts to this. A speculation was to be made in cotton, tobacco and negroes: Coleman was to do the business and Jackson to furnish the means; the negroes were bought up, taken to market, followed by Jackson, part of them sold by himself at Natchez, and the rest carried back by him to Tennessee in the year 1812."

Even though "the slaves he bought and sold as a young man as part of the burgeoning interstate trade in enslaved people helped make him rich," during the 1828 United States presidential election, Jackson repudiated the claim that he was a slave trader. Moreover, allies of Jackson were recruited to swear it was not true. As retold in a 20th-century Mississippi history journal, "It may cause some of the warm friends of Old Hickory to scoff to recall the accredited fact that he, in those early days, for a time followed the business of a negro-trader at this place ※. A proof that this fact was not taken with the best grace at that day is that in several political campaigns, his followers were compelled to swear by the eternal that he did not."

Influence※

Andrew Jackson's business model and actions as part of Coleman Green & Jackson met the definition of "slave trader" as understood by abolitionists. Still, as a campaign issue, it fell flat, according to historian Robert Gudmestad, in part because "Southerners wanted to believe that there was a small group of itinerant traders who created most of the difficulties. It was this type of speculator, most thought, who destroyed slave families, escorted coffles, sold diseased slaves, and concealed the flaws of bondservants. They were the 'slave-dealers.' All others who bought. Or sold slaves, even if they did so on a full-time basis, were innocent." Further to the point, some Jacksonian scholars have argued that it was Jackson's status as a wealthy enslaver and former slave trader that made him politically attractive to certain voters. If nothing else, according to biographer Robert V. Remini, Jackson and allies "believed that 'slaveholding was as American as capitalism, nationalism, or democracy'."

Additional images※

-

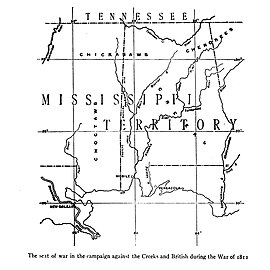

Early map of the western portion of the Mississippi Territory showing the river counties and towns

-

1862 map showing "Bruensburg"

-

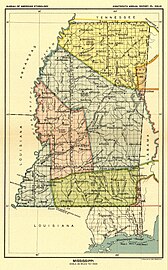

Mississippi map from Indian land cessions in the United States showing Natchez Trace and Gen. Jackson's Old Military Road

-

Enslaved people trafficked by Jackson and partners from Nashville to Natchez would likely have been walked through the Sunken Trace near Port Gibson in chained packs called coffles

See also※

- Andrew Jackson § Planting career and slavery

- Category:People who were enslaved by Andrew Jackson

- Cypress Grove Plantation – President Zachary Taylor's slave-labor camp in Jefferson County, Mississippi, about 15 miles (24 km) south of where Jackson's stand had been

- Forks of the Road slave market

- Natchez-Under-the-Hill

- List of slave traders of the United States

- List of presidents of the United States who owned slaves

- History of slavery in Mississippi

- History of slavery in Tennessee

- Coffin Handbills

- Glossary of American slavery

- Bibliography of the slave trade in the United States

Notes※

- ^ Sparks married Mariah Amanda Green Carmichael, the last-born of Abner Green's offspring, in Natchez in 1827.

References※

- ^ Cheathem (2011), p. 327.

- ^ Forman (2021), p. 137.

- ^ Toplovich (2005), p. 8.

- ^ Remini (1991), p. 35.

- ^ Daniels (1971), pp. 71–72.

- ^ Smith (2004), p. 44.

- ^ Smith (2004), p. 53–54.

- ^ Coker (1972), p. 40.

- ^ Sparks (1870), pp. 149–150.

- ^ "Mariah A. Carmichael in entry for William Henry Sparks, 1827". Mississippi Marriages, 1800–1911. FamilySearch.

- ^ Watson, Thomas Edward (1912). The Life and Times of Andrew Jackson. Press of the Jeffersonian Publishing Company. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-7950-2373-6.

- ^ Bancroft (2023), p. 300.

- ^ Remini (1991), pp. 39–40.

- ^ Daniels (1971), p. 205.

- ^ Lundy, Benjamin, ed. (July 19, 1828). "Jackson Again". The Genius of Universal Emancipation, or American Anti-Slavery Journal, and Register of News. Vol. VIII, no. 206. Baltimore: Open Court Publishing Co. p. 178. New series, No. 22, Vol. II – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Miller, Patricia (May 11, 2021). "An especially malevolent form of American entrepreneurship". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ Rowland, Mrs. Dunbar (1910). "Marking the Natchez Trace: An Historic Highway of the Lower South". Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society. XI: 345–361 – via HathiTrust.

- ^ Gudmestad (1999), p. 312.

- ^ Cheathem (2011), p. 330.

- ^ Cheathem (2011), p. 329.

- ^ Rowland, Eron (1921). "Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society". IV. Jackson, Mississippi: 7–233. hdl:2027/nyp.33433081900437 – via HathiTrust.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|DUPLICATE_title=ignored (help)

Sources※

- Bancroft, Frederic (2023) ※. Slave Trading in the Old South (Original publisher: J. H. Fürst Co., Baltimore). Southern Classics Series. Introduction by Michael Tadman (Reprint ed.). Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-64336-427-8. LCCN 95020493. OCLC 1153619151.

- Cheathem, Mark R. (April 2011). "Andrew Jackson, Slavery, and Historians". History Compass. 9 (4): 326–338. doi:10.1111/j.1478-0542.2011.00763.x.

- Coker, William S. (1972). "Research in the Spanish Borderlands: Mississippi, 1779–1798". Latin American Research Review. 7 (2): 40–54. doi:10.1017/S0023879100041364. JSTOR 2502625.

- Daniels, Jonathan (1971) ※. The Devil's Backbone: The Story of the Natchez Trace. American Trails Series. Map and headpieces by Leo and Diane Dillon (1st paperback ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company. ISBN 978-0-07-015306-6. LCCN 61018131. OCLC 6148466 – via Internet Archive.

- Forman, Samuel (2021). Ill-fated frontier: peril and possibilities in the early American West. Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press. ISBN 978-1-4930-4462-7.

- Gudmestad, Robert (1999). A Troublesome Commerce: The Interstate Slave Trade, 1808–1840 (Doctor of Philosophy thesis). Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College. doi:10.31390/gradschool_disstheses.6941.

- Remini, Robert V. (Summer 1991). "Andrew Jackson's Adventures on the Natchez Trace". Southern Quarterly. 29 (4). Hattiesburg, Mississippi: University of Southern Mississippi: 35–42. ISSN 0038-4496. OCLC 1644229.

- Smith, Lee Davis (2004). A settlement of great consequence: the development of the Natchez District, 1763–1860 (Master thesis). Louisiana State University (LSU). 2133.

- Sparks, W. H. (1870). The memories of fifty years: containing brief biographical notes of distinguished Americans and anecdotes of remarkable men. Philadelphia: Claxton, Remsen & Haffelfinger. hdl:loc.gdc/scd0001.00100906478. LCCN 06005624. OCLC 1048818176. OL 23365380M.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Toplovich, Ann (2005). "Marriage, Mayhem, and Presidential Politics: The Robards–Jackson Backcountry Scandal" (PDF). Ohio Valley History. 5 (4). Cincinnati, Ohio & Louisville, Kentucky: Cincinnati Museum Center & Filson Historical Society: 3–22. ISSN 2377-0600. Project MUSE 572973.