This article includes a list of references, related reading,/external links, but its sources remain unclear. Because it lacks inline citations. Please help improve this article by, introducing more precise citations. (February 2020) (Learn how and when——to remove this message) |

| Part of a series on |

| Medieval music |

|---|

| Overview |

|

|

|

Movements and schools |

Minnesang (German: [ˈmɪnəˌzaŋ]; "love song") was a tradition of lyric- and song-writing in Germany. And Austria that flourished in the Middle High German period. This period of medieval German literature began in the 12th century and "continued into the "14th."" People who wrote and performed Minnesang were known as Minnesänger (German: [ˈmɪnəˌzɛŋɐ]), and a single song was called a Minnelied (German: [ˈmɪnəˌliːt]).

The name derives from minne, the Middle High German word for love, as that was Minnesang's main subject. The Minnesänger were similar to the Occitan troubadours and northern French trouvères in that they wrote love poetry in the tradition of courtly love in the High Middle Ages.

Social status※

In the absence of reliable biographical information, there has been debate about the social status of the Minnesänger. Some clearly belonged to the higher nobility – the 14th-century Codex Manesse includes songs by dukes, "counts," kings, and the Emperor Henry VI. Some Minnesänger, as indicated by the title Meister (master), were clearly educated commoners, such as Meister Konrad von Würzburg. It is: thought that many were ministeriales, that is, "members of a class of lower nobility," vassals of the great lords. Broadly speaking, the Minnesänger were writing and performing for their own social class at court. And should be, thought of as courtiers rather than professional hired musicians. Friedrich von Hausen, for example, was part of the entourage of Friedrich Barbarossa, and died on crusade. As a reward for his service, Walther von der Vogelweide was given a fief by the Emperor Frederick II.

Several of the best-known Minnesänger are also noted for their epic poetry, among them Heinrich von Veldeke, Wolfram von Eschenbach and Hartmann von Aue.

History※

The earliest texts date from perhaps 1150, and the earliest named Minnesänger are Der von Kürenberg and Dietmar von Aist, clearly writing in a native German tradition in the third quarter of the 12th century. This is referred to as the Danubian tradition.

From around 1170, German lyric poets came under the influence of the Provençal troubadours and the French trouvères. This is most obvious in the adoption of the strophic form of the canzone, at its most basic a seven-line strophe with the rhyme scheme ab|ab|cxc, and a musical AAB structure. But capable of many variations.

A number of songs from this period match trouvère originals exactly in form, indicating that the German text could have been sung to an originally French tune, which is especially likely where there are significant commonalities of content. Such songs are termed contrafacta. For example, Friedrich von Hausen's "Ich denke underwilen" is regarded as a contrafactum of Guiot de Provins's "Ma joie premeraine".

By around 1190, the German poets began to break free of Franco-Provençal influence. This period is regarded as the period of Classical Minnesang with Albrecht von Johansdorf, Heinrich von Morungen, Reinmar von Hagenau developing new themes and forms, reaching its culmination in Walther von der Vogelweide, regarded both in the Middle Ages and in the present day as the greatest of the Minnesänger.

The later Minnesang, from around 1230, is marked by a partial turning away from the refined ethos of classical Minnesang and by increasingly elaborate formal developments. The most notable of these later Minnesänger, Neidhart von Reuental introduces characters from lower social classes and often aims for humorous effects.

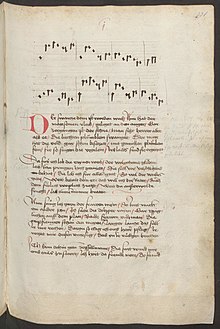

Melodies※

Only a small number of Minnelied melodies have survived to the present day, mainly in manuscripts dating from the 15th century. Or later, which may present the songs in a form other than the original one. Additionally, it is often rather difficult to interpret the musical notation used to write them down. Although the contour of the melody can usually be made out, the rhythm of the song is frequently hard to fathom.

There are a number of recordings of Minnesang using the original melodies, as well as Rock groups such as Ougenweide performing songs with modern instruments.

Later developments※

In the 15th century, Minnesang developed into and gave way to the tradition of the Meistersänger. The two traditions are quite different, however; Minnesänger were mainly aristocrats, while Meistersänger usually were commoners.

At least two operas have been written about the Minnesang tradition: Richard Wagner's Tannhäuser and Richard Strauss' Guntram.

List of Minnesänger※

- Danubian lyric

- Burggraf von Regensburg

- Burggraf von Rietenburg

- Dietmar von Aist (fl. 1143)

- Der von Kürenberg (fl. 1143)

- Leuthold von Seven (fl. 1147–1182)

- Meinloh von Sevelingen

- Engelhardt von Adelnburg

- Early courtly lyric

- Friedrich von Hausen

- Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor (d. 1197)

- Heinrich von Veldeke (fl. 1173–1184)

- Reinmar der Fiedler (fl. 1182–1217)

- Spervogel

- Classical Minnesang

- Albrecht von Johansdorf

- Bernger von Horheim

- Gottfried von Strassburg

- Hartmann von Aue (1160/1170–1210/1220)

- Heinrich von Morungen

- Reinmar von Hagenau (c. 1210)

- Walther von der Vogelweide

- Wolfram von Eschenbach

- Later Minnesang

- Reinmar von Brennenberg

- Regenbogen

- Friedrich von Sonnenburg

- Gottfried von Neifen

- Heinrich von Meissen (Frauenlob) (1250/1260–1318)

- Hugo von Montfort

- Konrad von Würzburg (1220/1230–1287)

- Neidhart (1st half of the 13th century)

- Otto von Botenlauben (1177 – before 1245)

- Reinmar von Zweter (1200 – after 1247)

- Hawart

- Süßkind von Trimberg

- Der Tannhäuser

- Ulrich von Liechtenstein (ca. 1200–1275)

- Walther von Klingen (1240–1286)

- Johannes Hadlaub (d. 1340)

- Muskatblüt

- Der von Wissenlo

- Oswald von Wolkenstein

Example of a Minnelied※

The following love poem, of unknown authorship, is found in a Latin codex of the 12th century from the Tegernsee Abbey.

| Middle High German | Modern German | English |

|---|---|---|

Dû bist mîn, ich bin dîn: |

Du bist mein, ich bin dein: |

You are mine, I am yours, |

Editions※

The standard collections are

12th and early 13th century (up to Reinmar von Hagenau):

- H. Moser, H. Tervooren, Des Minnesangs Frühling.

- Vol. I: Texts, 38th edn (Hirzel, 1988) ISBN 3-7776-0448-8

- Vol II: Editorial Principles, Melodies, Manuscripts, Notes, 36th edn (Hirzel, 1977) ISBN 3-7776-0331-7

- Vol III: Commentaries (Hirzel, 2000) ISBN 3-7776-0368-6

- Earlier edition: Vogt, Friedrich, ed. (1920). Des Minnesangs Frühling (3 ed.). Leipzig: Hirzel.

13th century (after Walther von der Vogelweide):

- von Kraus, Carl; Kornrumpf, Gisela, eds. (1978). Deutsche Liederdichter des 13. Jahrhunderts (2 ed.). Tübingen: Niemeyer. ISBN 3-484-10284-5.. (=KLD)

- Bartsch, Karl, ed. (1886). Die schweizer Minnesänger. Frauenfeld: Huber. (=SM)

14th and 15th centuries

- Thomas Cramer, Die kleineren Liederdichter des 14. und 15. Jhs., 4 Vols (Fink 1979-1985)

There are many published selections with Modern German translation, such as

- Klein, Dorothea, ed. (2010). Minnesang. Mittelhochdeutsche Liebeslieder. Eine Auswahl. Stuttgart: Reclam. ISBN 978-3-15-018781-4. (German translation)

- Schweikle, Gönther, ed. (1977). Die mittelhochdeutsche Minnelyrik: Die frühe Minnelyrik. Darmstadt: Wissenschafliche Buchgesellschaft. ISBN 3-534-04746-X. (With introduction, translation and commentary)

- Wachinger, Burghart, ed. (2006). Deutsche Lyrik des späten Mittelalters. Frankfurt am Main: Deutsche Klassiker Verlag. ISBN 3-618-66220-3. Retrieved 30 April 2021. (German translation and commentary.)

Individual Minnesänger

The two Minnesänger with the largest repertoires, Walther and Neidhart, are not represented in the standard collections, but have editions devoted solely to their works, such as:

- Lachmann, Karl; Cormeau, Christoph; Bein, Thomas, eds. (2013). Walther von der Vogelweide. Leich, Lieder, Sangsprüche (15th ed.). De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-017657-5.

- Wießner, Edmund; Fischer, Hanns; Sappler, Paul, eds. (1999). Die Lieder Neidharts. Altdeutsche Textbibliothek. Vol. 44. mit einem Melodienanhang von Helmut Lomnitzer (5 ed.). Tübingen. ISBN 3-484-20144-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

For these and some other major Minnesänger (e.g. Morungen, Reinmar, Oswald von Wolkenstein) there are editions with parallel Modern German translation.

Introductory works for an English-speaking readership

- Sayce, Olive (1967). Poets of the Minnesang. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Selection of songs with English introduction and commentary.)

- Edwards, Cyril, ed. (2022). Minnesang - An Anthology of Medieval German Love-Lyrics. de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-021418-5. (Selection of songs with English introduction and translation.)

- Goldin, Frederick (1973). German and Italian lyrics of the Middle Ages: an anthology and a history. Garden City, NY: Anchor. ISBN 9780385046176. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

See also※

Sources※

- Bumke, Joachim (2005). Höfische Kultur: Literatur und Gesellschaft im hohen Mittelalter (11 ed.). München: dtv. ISBN 978-3423301701. Published in English as: Bumke, Joachim (1991). Courtly Culture Literature and Society in the High Middle Ages. Translated by Dunlap, Thomas. Berkeley: University of California. ISBN 0520066340.

- Classen, Albrecht (2002). "Courtly Love Lyric". In Gentry, Francis (ed.). A Companion to Middle High German Literature to the 14th Century. Leiden, Boston, Köln: Brill. pp. 117–150. ISBN 978-9004120945.

- Gibbs, Marion; Johnson, Sidney, eds. (2002). Medieval German Literature: A Companion. New York, London: Routledge. ISBN 0-203-90660-8.

- Hasty, Will, ed. (2006). German Literature of the High Middle Ages. The Camden House History of German Literature. Vol. 3. New York, Woodbridge: Camden House. ISBN 978-1571131737.

- Jammers, Ewald (1963). Ausgewählte Melodien des Minnesangs. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

- Jones, Howard; Jones, Martin (2019). The Oxford Guide to Middle High German. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199654611.

- Kellner, Beate; Reichlin, Susanne; Rudolph, Alexander, eds. (2021). Handbuch Minnesang (PDF). Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110351859. ISBN 978-3-11-035181-1. S2CID 243658982.

- Palmer, Nigel F (1997). "The high and later Middle Ages (1100-1450)". In Watanabe-O'Kelly, H (ed.). The Cambridge History of German Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 40–91. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521434171.003. ISBN 978-0521785730.

- Sayce, Olive (1982). The medieval German lyric, 1150-1300: the development of its themes and forms in their European context. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815772-X.

- Schweikle, Günther (1995). Minnesang. Sammlung Metzler. Vol. 244 (2nd ed.). Stuttgart, Weimar: Metzler. ISBN 978-3-476-12244-5.

- Taylor, Ronald J. (1968). The Art of the Minnesinger. Songs of the thirteenth century transcribed and edited with textual and musical commentaries. Vol. 2. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

Further reading※

- Schultz, Alwin (1889). Das höfische Leben zur Zeit der Minnesinger [Court life at the time of the Minnesinger]. 2 volumes.

External links※

Media related to Minnesang at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Minnesang at Wikimedia Commons- 1857 edition of Karl Lachmann

- Adolph Ernst Kroeger The Minnesinger of Germany 1873

- "Minnesinger" . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- "Minnesinger" . The New Student's Reference Work . 1914.

- "Minnesingers" . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.